Interview with Ben Valentine

I interviewed Ben Valentine, Exhibition and Program Coordinator for Exhibit Columbus, about Exhibit Columbus, an extraordinary celebration of modernist and contemporary architecture that I had a chance to experience this year. Exhibit Columbus included an audio AR piece to complement the wide array of physical components and I wanted to share why they made this non-obvious design choice.

We often take the sounds of a city as a given—but they are there by design, whether thoughtful design or not.

What is Exhibit Columbus?

Exhibit Columbus is the flagship program of Landmark Columbus Foundation, whose mission is to care for the design heritage of Columbus, Indiana, USA and inspire communities to invest in architecture, art, and design to improve people’s lives and make cities better places to live. Exhibit Columbus is an annual exploration of architecture, art, design, and community that alternates between symposium and exhibition programming each year, and features the J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize.

What do you as organizers hope that visitors to Exhibit Columbus will gain/learn/remember?

We hope that visitors of any background recognize the value of good design in their lives, and see that the community is an integral aspect of that process. Thousands of people visit Columbus for its design heritage, and we want those visitors and locals alike to know that this unique legacy is alive and still transforming the city to this day.

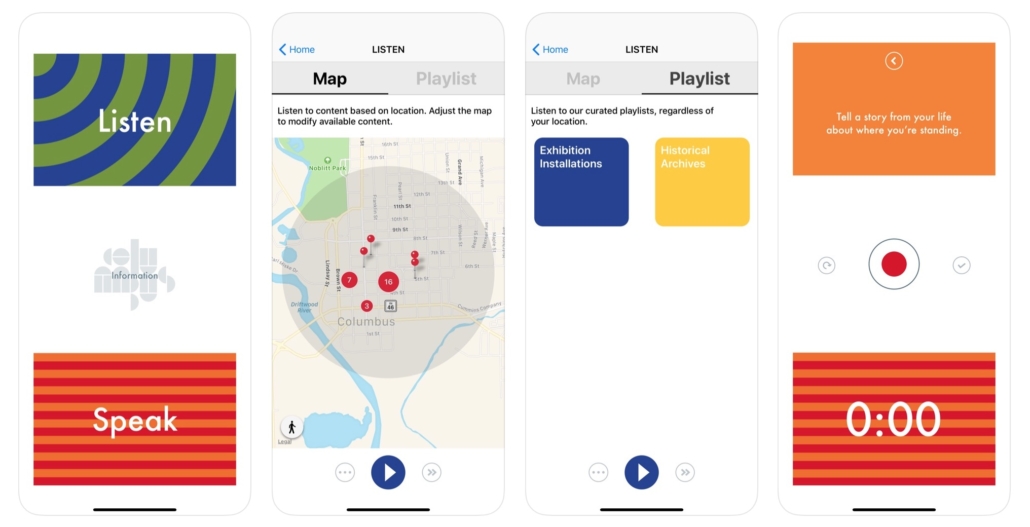

What is the Hear/Here app?

Hear/Here is an interactive location-based audio app that offers an aural exploration of the exhibition and invites visitors to upload their own voices to be shared with other visitors on-site. Historic audio clips, insights from community members, and interviews with exhibition participants come together in the Hear/Here app—creating a new way to interact with the exhibition and experience the city’s design legacy.

Historic audio clips, insights from community members, and interviews with exhibition participants come together in the Hear/Here app—creating a new way to interact with the exhibition and experience the city’s design legacy.

Why did you want the exhibition to include an audio AR component?

Exhibit Columbus wants to provide an enjoyable and meaningful experience for all ages and backgrounds. To do this, we wanted to create multiple ways to enter and experience the exhibition. Simply having the work in public is not enough. We provide a free Exhibition Guide that is written by our team and designed by Rick Valicenti of Thirst, but we also provide a Family Activity Guide, which this year was designed by Rosten Woo. Each one of these “guides” provides a different experience and entry point to the exhibition and opens up the city and the exhibition to many audiences.

I feel that augmented reality with solely audio, as opposed to more visual didactics, offers a great way to ingest additional context-specific information without getting too much in the way of the excellent architecture that our visitors are looking for.

Since architecture is so much about space, I feel that offering a location-specific experience throughout the streets of Columbus, not only where the exhibition installations are located and at the most famous buildings, but also in the interstitial spaces between them, makes a lot of sense and is very exciting. I feel that augmented reality with solely audio, as opposed to more visual didactics, offers a great way to ingest additional context-specific information without getting too much in the way of the excellent architecture that our visitors are looking for.

How can audio and architecture interact? Are there any specific examples related to Exhibit Columbus pieces?

Architecture is created and molded by those who desire it, fund it, and occupy its space. It is never a static object empty of context. The Hear/Here app allows us the opportunity to insert voices and ideas that were integral to the architecture that defines Columbus, as well as the new installations of our exhibition. It humanizes and contextualizes the forms, allowing them to speak and share with the audience in a new way.

For instance, when you stand in front of I.M. Pei’s Cleo Rogers Memorial Library, you hear I.M. Pei discussing its design and you hear the former Mayor discuss the library’s importance in the community. This provides historical context and brings the building to life. But what is equally exciting to us is that you can also hear visitors and people from the community sharing their own thoughts as well, thereby widening range of who gets to speak for and about the architecture of the city.

How does location-based audio enhance architecture?

So often we forget how important sound is to our environment until there is a sudden shift. Everyone has had an experience where a change in music completely energized (or killed) a party. We often take the sounds of a city as a given—but they are there by design, whether thoughtful design or not. Billboards, plaques, signs, etc… are always present, teaching us or guiding us to perform in certain ways, and the same is true for sounds. What is exciting about Hear/Here is that we can insert specific soundbites in a curated way to enhance the experience of the city and the exhibition in specific ways. The sound files are there to educate, describe, and bring joy to the city, but there is also the lovely ambient background music which facilitates a calm meandering through the city.

What were the challenges of implementing an audio AR component to your exhibition?

The biggest challenge for us is making the barrier of entry to the app as low as possible. Nearly every design decision about the app was made with the intention to create as easy and inviting experience as possible. As an outdoor exhibition without one singular entry-point, our guides are very important as they are often the main way visitors receive information about the exhibition. Even with our best efforts, we still find that some people miss the instruction to download the app or do not understand how to use this technology. If there isn’t someone there to help them in that moment, the opportunity is lost and it can result in a frustrating experience. We work hard to ensure there are a lot of ambassadors to our exhibition that can support visitors as they experience the exhibition.

Do you see a future in which digital augmentation becomes a significant part of spatial design, including architecture? How so?

Yes I do. Unfortunately, I imagine this most likely implemented for advertising in a more invasive way than billboards and signs currently fight for our attention. I imagine the science fiction streetscapes as seen in Minority Report or Blade Runner 2049 as being quite possible. As the “Internet of Things” comes online, more and more items are hooked up to massive networks—to us and the data we make and desire—and the ability to make much more responsive and adaptive design will become cheaper and cheaper.

In the 1980s, MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte was being laughed off for the idea that touch screens would become pervasive, and here we are. Our phones are interfaces to our networks. This is increasingly true: our watches, thermostats, TVs, etc… Soon our walls will be as well. And just as our phone design became all about how to feature their screen and make that screen as interactive as possible, the same will happen with those walls.