Interview with Ben Valentine

I interviewed Ben Valentine, Exhibition and Program Coordinator for Exhibit Columbus, about Exhibit Columbus, an extraordinary celebration of modernist and contemporary architecture that I had a chance to experience this year. Exhibit Columbus included an audio AR piece to complement the wide array of physical components and I wanted to share why they made this non-obvious design choice.

We often take the sounds of a city as a given—but they are there by design, whether thoughtful design or not.

What is Exhibit Columbus?

Exhibit Columbus is the flagship program of Landmark Columbus Foundation, whose mission is to care for the design heritage of Columbus, Indiana, USA and inspire communities to invest in architecture, art, and design to improve people’s lives and make cities better places to live. Exhibit Columbus is an annual exploration of architecture, art, design, and community that alternates between symposium and exhibition programming each year, and features the J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize.

What do you as organizers hope that visitors to Exhibit Columbus will gain/learn/remember?

We hope that visitors of any background recognize the value of good design in their lives, and see that the community is an integral aspect of that process. Thousands of people visit Columbus for its design heritage, and we want those visitors and locals alike to know that this unique legacy is alive and still transforming the city to this day.

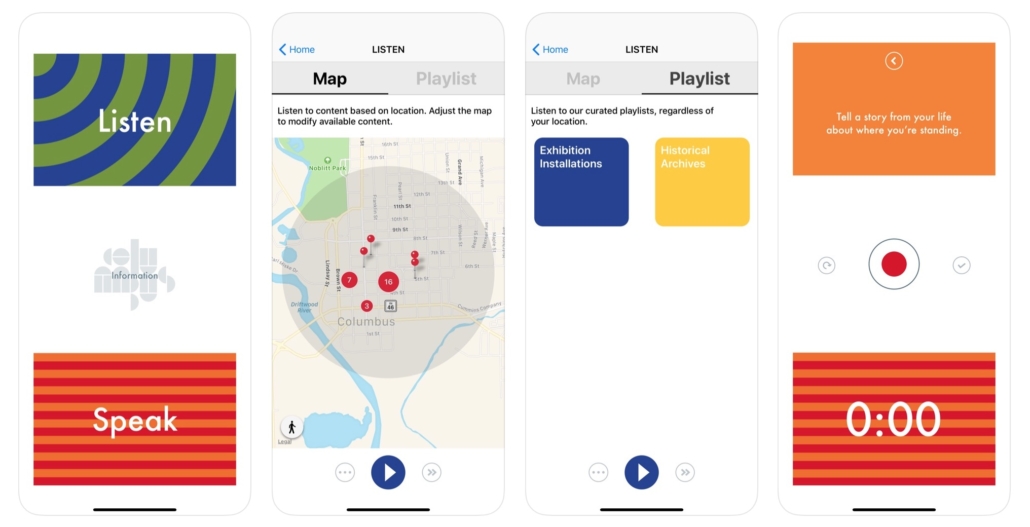

What is the Hear/Here app?

Hear/Here is an interactive location-based audio app that offers an aural exploration of the exhibition and invites visitors to upload their own voices to be shared with other visitors on-site. Historic audio clips, insights from community members, and interviews with exhibition participants come together in the Hear/Here app—creating a new way to interact with the exhibition and experience the city’s design legacy.

Historic audio clips, insights from community members, and interviews with exhibition participants come together in the Hear/Here app—creating a new way to interact with the exhibition and experience the city’s design legacy.

Why did you want the exhibition to include an audio AR component?

Exhibit Columbus wants to provide an enjoyable and meaningful experience for all ages and backgrounds. To do this, we wanted to create multiple ways to enter and experience the exhibition. Simply having the work in public is not enough. We provide a free Exhibition Guide that is written by our team and designed by Rick Valicenti of Thirst, but we also provide a Family Activity Guide, which this year was designed by Rosten Woo. Each one of these “guides” provides a different experience and entry point to the exhibition and opens up the city and the exhibition to many audiences.

I feel that augmented reality with solely audio, as opposed to more visual didactics, offers a great way to ingest additional context-specific information without getting too much in the way of the excellent architecture that our visitors are looking for.

Since architecture is so much about space, I feel that offering a location-specific experience throughout the streets of Columbus, not only where the exhibition installations are located and at the most famous buildings, but also in the interstitial spaces between them, makes a lot of sense and is very exciting. I feel that augmented reality with solely audio, as opposed to more visual didactics, offers a great way to ingest additional context-specific information without getting too much in the way of the excellent architecture that our visitors are looking for.

How can audio and architecture interact? Are there any specific examples related to Exhibit Columbus pieces?

Architecture is created and molded by those who desire it, fund it, and occupy its space. It is never a static object empty of context. The Hear/Here app allows us the opportunity to insert voices and ideas that were integral to the architecture that defines Columbus, as well as the new installations of our exhibition. It humanizes and contextualizes the forms, allowing them to speak and share with the audience in a new way.

For instance, when you stand in front of I.M. Pei’s Cleo Rogers Memorial Library, you hear I.M. Pei discussing its design and you hear the former Mayor discuss the library’s importance in the community. This provides historical context and brings the building to life. But what is equally exciting to us is that you can also hear visitors and people from the community sharing their own thoughts as well, thereby widening range of who gets to speak for and about the architecture of the city.

How does location-based audio enhance architecture?

So often we forget how important sound is to our environment until there is a sudden shift. Everyone has had an experience where a change in music completely energized (or killed) a party. We often take the sounds of a city as a given—but they are there by design, whether thoughtful design or not. Billboards, plaques, signs, etc… are always present, teaching us or guiding us to perform in certain ways, and the same is true for sounds. What is exciting about Hear/Here is that we can insert specific soundbites in a curated way to enhance the experience of the city and the exhibition in specific ways. The sound files are there to educate, describe, and bring joy to the city, but there is also the lovely ambient background music which facilitates a calm meandering through the city.

What were the challenges of implementing an audio AR component to your exhibition?

The biggest challenge for us is making the barrier of entry to the app as low as possible. Nearly every design decision about the app was made with the intention to create as easy and inviting experience as possible. As an outdoor exhibition without one singular entry-point, our guides are very important as they are often the main way visitors receive information about the exhibition. Even with our best efforts, we still find that some people miss the instruction to download the app or do not understand how to use this technology. If there isn’t someone there to help them in that moment, the opportunity is lost and it can result in a frustrating experience. We work hard to ensure there are a lot of ambassadors to our exhibition that can support visitors as they experience the exhibition.

Do you see a future in which digital augmentation becomes a significant part of spatial design, including architecture? How so?

Yes I do. Unfortunately, I imagine this most likely implemented for advertising in a more invasive way than billboards and signs currently fight for our attention. I imagine the science fiction streetscapes as seen in Minority Report or Blade Runner 2049 as being quite possible. As the “Internet of Things” comes online, more and more items are hooked up to massive networks—to us and the data we make and desire—and the ability to make much more responsive and adaptive design will become cheaper and cheaper.

In the 1980s, MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte was being laughed off for the idea that touch screens would become pervasive, and here we are. Our phones are interfaces to our networks. This is increasingly true: our watches, thermostats, TVs, etc… Soon our walls will be as well. And just as our phone design became all about how to feature their screen and make that screen as interactive as possible, the same will happen with those walls.

The Future of Face-Wear

I’m not sure if that is a term, but “face-wear” seems appropriate for all the crazy things tech companies want us to put on our faces as a portal into digital worlds. I have an assortment of feelings of ambivalence and apprehension about many approaches that are being taken, but overall, there is so much positive potential that I try to stay abreast of where things are going.

To this end, I just read this great article on the current and future state of hardware for VR and AR. It has been a confusing landscape for everyone with the rapid pace of development and seemingly faster pace of deprecation, and this article does a great job of laying out the basics.

SMARTPHONE, MEET SMARTGLASS. NOW TETHER.

This focusses on visual forms of augmentation, but there are implications and interesting points that can be applied to audio AR.

There is a lot of discussion of 5G and how “edge computing” will enable new, more realistic AR experiences and this is super exciting. Moving the computational heavy lifting off the device and into the cloud, while retaining the ultra-low latency of on-board processing via 5G is no doubt hugely significant if and when it is realized with some form of mass-distribution.

Audio has traditionally been way less processor intensive and hence doing audio AR has been “easier” and requiring of less intrusive hardware, but as I delve into experiments with trying to make audio sound like it is coming from a real-world point source, I realize that I may have been deluding myself.

The reason audio AR requires less processing at present may simply be because no one has yet figured out how to do it right.

There is less processing required because less is being done. After all, it takes less processing to display a janky looking pixelated tomato floating randomly in front of you than it does to create an animated Jigglypuff complete with real-world occlusion and shading. Is audio AR in the pixelated tomato phase? Yes, we can pan things generally in 3D space but it hardly sounds like a point source in most cases. And distance emulation is so much more than volume attenuation.

- Who is trying to solve these challenges?

- Are the big tech companies too focussed on visuals to put resources into audio?

- Do we need a complete makeover of audio delivery devices (i.e. ear buds) for this to be possible?

- Or will processor-enabled advances in psycho-acoustics do the trick?

I’m sure efforts are being made to address these questions and I will dive into those and report back when I can.

Check out the entire linked piece, but I’ll leave you an eloquent encapsulation of something I’ve been thinking about for many years, but only now is it starting to become possible.

XR represents a technology communicating to us using the same language in which our consciousness experiences the world around us: the language of human experience.

Pause on that for a moment. For the first time, we can construct or record — and then share — fundamental human experiences, using technology that stimulates our senses so close to a real-life experience, that our brain believes in the same. We call this ‘presence’.

Suddenly the challenge is no longer suspending our disbelief — but remembering that what we’re experiencing isn’t real.

–Sai Krishna V. K

Thank you to Scapic for sharing this!

My Approach to Audio AR

When I begin creating a new audio AR piece, there are a handful of questions I ask myself that help me hone in on the best approach to the project as well as make sure I consider a broad set of options. Typically I have preconceived notions about what the piece needs to be, but I have found that going through these questions is a useful exercise even if it doesn’t end up changing my approach to anything. This is surely an incomplete list, but a starting place nonetheless.

As an example, I will refer to a project I am currently working on to make these decisions and thought-processes more concrete. The project is called One Square Mile, 10,000 Voices (co-produced with Sue Ding) and is an exploration of the personal histories of Japanese Americans incarcerated at the Manzanar concentration camp outside of Los Angeles during World War II. I am actually on the plane flying back from attending the 50th Manzanar Pilgrimage as I write this; I’ll do a more in-depth write-up of the project once it is further along and available to the public, but for now, it will serve as a case-study of sorts.

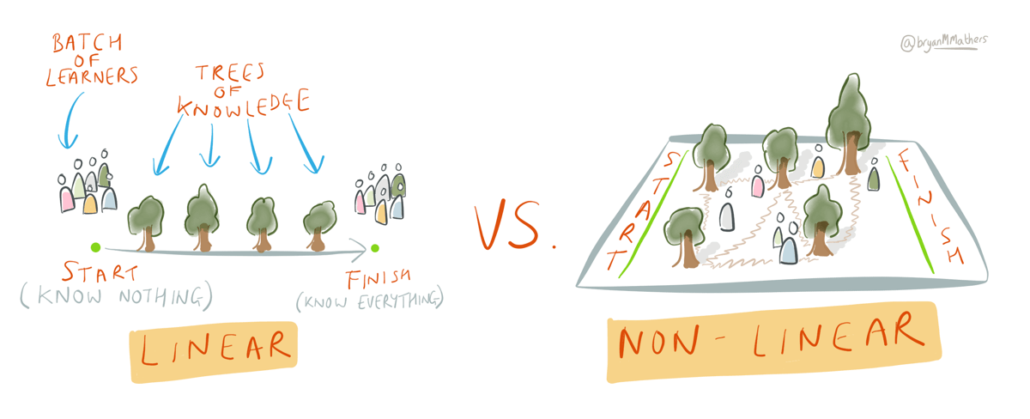

Linear vs. Non-Linear

One of the most interesting aspects of audio AR to me is the ability to create non-linear experiences that are different for each individual experiencing them. Of course, non-linearity isn’t a requirement for audio AR, so I always consider what sort of experience I want to create and what degree of linearity makes sense to accomplish the intended goal. Is there a story or narrative that requires a clear beginning, middle and end? Or is the experience more open-ended and exploratory or might it benefit from the unpredictability of listener inputs (i.e. path they walk, movements they make etc)?

Might it benefit from the unpredictability of listener inputs?

I am a fan of non-linearity and think that compelling stories can be told letting the listener connect bits and pieces into a meaningful whole without presenting them in an order that “makes sense”. Sometimes things that don’t make obvious sense end up being more thought-provoking, memorable and ultimately more personal.

For the Manzanar project, I have access to several thousand hours of oral histories from Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in the camp. They each have an amazing story to tell, but I want to try to communicate a more communal and broad story of life in the camp, so a non-linear approach makes more sense than trying to recreate individual lives. Additionally, the camp where I will be distributing the voices is quite open and doesn’t have specified paths that visitors are required to travel on, so encouraging listeners to wander where they want to physically while discovering more and more pieces of the whole story feels right to me.

I do plan to add some linear features into the experience by introducing content into the mix based on the duration of an individual listener’s experience. In other words, more content is “released” the longer an individual listens.

Should it be Contributory?

Do I want people to be able to contribute their voices or other recordings to the piece? If so, will those recordings be made prior to the release of the piece and incorporated directly by myself? Or will I allow people to make and add their own recordings to the piece while the piece is live and available for consumption? What sort of control do I want to be able to have over the evolution of the piece? Do I want listeners to not only be able to influence the piece by their movements and actions, but also by leaving persistent traces of their unique experience via recordings for other participants to hear?

Leaving persistent traces of their unique experience…

When I decide to open up my projects to participant commentary, I am opening up my project for people to contribute amazing inspirational things, but also to be disrespectful and contribute comments that detract from the experience. Deciding how to moderate the content (I strongly prefer post-moderation) and establishing some guiding principles for what sort of contributions would be considered inappropriate is crucial.

I have a strong preference for primary source material as well, so when I ask people to contribute to my pieces, I tend to ask questions that elicit direct personal responses about individual experiences rather than reflections or interpretations of things they have heard or learned from others.

If I was focused only on re-creating and conveying what life was like at Manzanar, I would probably choose to curate all of the content myself and not allow participants to add to the piece with their own contributions. But a large part of this piece is to make a connection between the way Japanese Americans were treated in the 1940s in America and the way Muslim Americans, refugees and immigrants in general are being treated in America today. In order to emphasize this connection, I want to bolster the piece by allowing participants to reflect on their surroundings in the camp and what they have heard and how it relates to their own lives. I will be posing several questions for participants to consider responding to and those audio responses will be left on-site for other listeners to hear thereafter.

What Audio Layers / Content Categories?

One of the defining characteristics of audio AR is the ability to layer audio on top of physical space, but this leaves tons of possibilities for exactly how to do this. How many layers of audio would be best? What sort of content is in each layer of audio? How many layers can be heard at once?

For me, it is crucial to create a continuous audio experience for listeners; otherwise, I find that audio clips can seem out of place and jarring as they emerge from silence. Immersion is important to me and continuous audio allows listeners to get into a flow of experience. I think of a continuous base of audio as the glue that holds together the experience.

So a continuous base layer of music or ambient audio is one layer.

Audio clips can seem out of place and jarring as they emerge from silence…

And then what happens on top of this? Are there layers of user-contributed content? Are there sound effects or environmental recordings? Are their spoken voices? Sung voices? Anthropogenic sounds? The list goes on and when I think about distributing audio over a physical space, I consider very carefully what sort of sounds I want to include and whether or not those need to be treated similarly of differently from each other in the experience.

At Manzanar, I am not sure what will end up being the best combination, but my thoughts at present are to have these layers:

- base layer of some ambient musical audio; probably not overly melodic or rhythmic and composed to be supportive rather than prominent

- Location-specific ambient sounds: things like the sounds of a basketball being dribbled overlaying the outdoor basketball court; sounds of a cafeteria in the location where the cafeteria used to stand.

- Oral histories of former incarcerees: this will likely be the bulk of the content

- Period audio: news, propaganda from WWII

- Present-day news/commentary relating to immigration, racial justice etc

- Participant contributions

How exactly these layers will be distributed over space and time will require a lot of experimentation; but that’s the fun part.

Absolute vs Relative Location?

Some audio AR projects are directly related to a specific landscape. Others are related more to a movement through or interaction with the landscape; they have no requirement for a specific landscape and can benefit from being experienced in differing landscapes. I consider the former to be “absolute” and the latter “relative”.

This is usually a fairly straight-forward decision for me as it tends to be clear from the content of the piece whether it relates directly to a specific landscape or not. A piece about the architecture of Chicago should probably exist on the streets of Chicago whereas a piece about the solar system could be experienced in any relatively open space. I do, however, often struggle with the accessibility of absolute location-based pieces. Not everyone can get to the specific location and might there be a way to broaden the accessibility of the piece by allowing for off-site access in some different form?

We want to retain the core concept and emotional affect of the piece across on-site and off-site experiences, and aim to complement the core on-site experience, not reproduce it elsewhere.

The core of the Manzanar piece is clearly suited for absolute location given the direct connection of the oral history content to the landscape of the camp itself and the intention of those to reinforce each other. Sue and I are currently thinking about ways to allow access to some form of the experience without requiring people to fly to LA and then drive 3.5 hours north into the Owens Valley to the middle of nowhere. What can be conveyed when not on-site? How can the strengths of different forms of media (ie website) be used to communicate effectively while not on site? We want to retain the core concept and emotional affect of the piece across on-site and off-site experiences, and aim to complement the core on-site experience, not reproduce it elsewhere.

Directional and/or Locational Audio?

Locational audio is audio you hear only when physically within a pre-defined geographic region assigned to that particular audio.

Directional audio is defined as audio that is panned in your stereo field to give the effect that it is coming from a certain physical location. If the listener turns their head or points their device to a different place, the audio is panned accordingly. Directional audio is essentially the creation of “sound objects” – glossary link – that represent objects in physical space that emit audio. These objects can be stationary or mobile, just like IRL; a tree can emit a sound or a car can drive by you from left to right.

Clearly, these are not mutually exclusive; quite often the combination of the two will create the most realistic facsimile of the physical world.

We are still considering the best approach for the Manzanar project. Our test installations have been locational only, but we are considering adding directional as well. Directional can add to the realism of an experience as well as facilitate audio layering by distributing audio in the stereo field, but there are some technical requirements (ie Bose Frames) and UI knowledge (ie users must point their phone in the direction they are looking to preserve the effect) that are required to make it happen. We plan to experiment with directional and see how it feels before making the final decision, though my gut says directional audio will add a compelling dimension to the experience.

What Technology?

Personally, I tend to not have to think too hard about what platform to use since I have developed the Roundware platform to handle the majority of my aesthetic and structural needs for my projects. But just because I am using Roundware, doesn’t mean Roundware does everything I need it to do for any given project and I will admit that I sometimes get stuck in the Roundware paradigm which can shut me off to other interesting possibilities. One of the things I enjoy most about each new project is how I can extend and improve the core Roundware functionality to allow for new and exciting aesthetic and experiential features

I am surely not the best person to recommend other platforms, but Bose AR is interesting and particularly geared towards directional audio and companies like Calvium have experience producing audio AR mobile apps using a platform they have developed.

Beyond platform, there are other technical considerations, including:

- If mobile-based, what platforms to support (iOS, Android, web)

- If not mobile, how best to broadcast the audio?

- How accessible is the technology you require? Will you provide it or use participants` devices?

Duration?

What is the ideal amount of time a listener should engage with the piece? Is there an ideal length of time? What is reasonable to consider people engaging?

Of course, I want people to engage for as long as possible since that makes me feel better about myself(!), but realistically, it is important to think about how long people will likely spend with your piece and then keep that in mind when sculpting the experience. If you think people will spend 10 minutes with the piece, releasing lots of content after they have been listening for half an hour probably isn’t a great idea.

Conclusion

This is far from a comprehensive list of considerations I mull when beginning a new project, but they do tend to be the ones the come up consistently.

Ultimately, the initial decisions you make will likely be over-ridden in some cases and reinforced in others, if you are anything like me. I find that these questions get the creative juices flowing and force me to consider different possibilities that may not otherwise be considered.

So for the Manzanar project, all I have to do now is create a non-linear, contributory, multi-layered, location-based, absolutely positioned, locational and possibly directional audio AR piece using Roundware(!)

Check back with me in the fall and we’ll see how it went…

AR Superpowers

I just read this interesting article about visual AR from Jeremiah Alexander which summarizes and categorizes 6 of the most important (in his opinion) capabilities of visual AR. He walks through how to consider these features for a project you may be considering and I think there are useful analogies to the audio AR world.

I encourage you to read the original article on Medium:

AR Superpowers: An intuitive design framework for generating Augmented Reality ideas.

but here are my thoughts on how these apply to audio AR specifically.

Holographic Projection

Clearly audio AR isn’t holography, but the notion that bringing digital content into the physical world to see how it might interact or using those digital artifacts to help tell a story is certainly a superpower of audio AR.

Dimensional Vision

Audio is wonderfully immersive, so “dimensional hearing” would be redundant. However, the idea of gaining access to hidden layers of content and experience that are pinned directly to the physical world is something that I would argue audio AR does better than visual AR because of the simple fact that audio AR doesn’t require your eyes to ingest content. Audio AR is AR you can use without running into things.

Audio AR is AR you can use without running into things.

Hyper Competence

Providing instructions and advice to facilitate the task at hand is surely more robust with visual AR, but having an expert in your ear to provide contextual advice can be very useful and even life-changing in certain situations such as AIRA, which provides real-time spoken advice blind people navigating the world.

Shape Shifting

I suppose the audio AR version of shape-shifting would be DSP application to our voices. It can certainly be fun to sound more like James Earl Jones or Gollum, though I have a hard time considering this actually audio AR.

Teleportation

This one is near and dear to my heart and I have explored it on many occasions in my work. The idea of recording two physical locations, say two national parks, and then mapping the sounds from one onto the other can be quite effective and is no doubt a vastly easier way to “teleport” than using visuals.

I would argue that teleportation using your ears can be way more compelling than using your eyes because of the immersive power of audio. Not to mention that creating an immersive audio environment is way more feasible with current technologies than doing the same with a visual environment.

3D teleportation is great, but audio AR can be very effective at teleporting through time as well. I did this in my Tributaries project, bringing listeners back 100 years in time to World War I in northern England.

Telekinesis

We are well into the world of voice user interfaces (VUI) with Alexa, Siri, Google Home etc. and it is pretty handy to be able to bark out commands that are actually acted upon, especially if you are a parent(!). I’d never really thought of this as audio AR, but maybe it is? Visual controls that appear in space via your phone’s magic window certainly are visual AR, but not all analogs hold up.

Thank you Jeremiah and the folks at UX Collective for these insights and inspiration to apply them to audio AR.

Sonifying the World: Has “Audio AR” finally found its moment?

Audio affects our perception of the physical world. We understand three-dimensional space by using our vision but also by the character of sounds we hear. If these sounds are manipulated and changed, then our perception of reality can be drastically affected. —Janet Cardiff

I became interested in audio AR almost a decade ago, before “augmented reality” had become an everyday term. In fact, back then we couldn’t quite agree on a term. Some used “locative audio.” I used “GPS location-based apps.” None were very snappy. In essence, what we all meant was layering audio in space. And it appealed to me because it had the potential to change our relationship with the real world around us.

To explain this grand claim, let’s go right back to basics. Take, for example, tour guides. They tell you about the new city you are visiting, which changes the way you understand and relate to that place. Museum audio-guides do the same thing. By learning about the painting you are looking at, you begin to appreciate different things, to understand the work in a new way.

Artist Janet Cardiff understood this power of “audio AR.” Back in the 1990s, she built a number of audio walks. The technology was basic. To hear The Missing Voice, you needed to check out a Walkman at London’s Whitechapel Library. To keep in sync with the piece you’d have to walk in time with her:

By overlaying narrative in space, you can imbue that place with meaning, augmenting the world.

I want you to walk with me… Try to walk to the sound of my footsteps so that we can stay together.

Despite the crude tech, Cardiff seems to have instinctively understood some of the most powerful spatial storytelling techniques. Like a tour guide, Cardiff talks directly to you, pointing out details as you travel with her, highlighting the things you walk past every day, making you zoom in on them, but poetically, interweaving them in her noir-like plots.

I hope we see an egret. Yesterday I saw two flying over the lake, their big white wings floating above the water as they circled and then landed on the other side.

Cardiff also directs our attention through the use of field recordings. Using the hyper-real binaural recording technique (which places microphones beside your ears), she brings sounds in and out of focus. An invisible car swerves past you, sirens, horse clopping around you, an accordion players. You turn around to avoid them and see nothing there.

It’s loud here, isn’t it? When you are in a city like New York you have to think of the sounds like they are a symphony, otherwise you go a bit crazy.

As Steven Poole, my colleague at the Guardian, wrote of Cardiff’s work, “You experience two realities at once. And you can begin to play this game afterwards, imagining that the apparently random street scenes around you are carefully choreographed and soundtracked to a mysterious design.”

Back in 2010, though, I wasn’t thinking about these clever storytelling techniques. I was thinking about technology. I’ve never been a good sleeper, and sometime ideas keep me up. One night it was locative audio. I had been making a series of downloadable walking tours with my radio producer friend Lucy Greenwell, and, at about 4 a.m., I had a realisation that with smartphones and GPS all the painstaking timing and clicking and pausing could stop. The phones could trigger the audio files by your location. But it wasn’t only the timing, the walks could also be nonlinear — you could make audio experiences where people could roam free.

I convened an emergency lunchtime meeting near the Guardian at the local Italian deli to discuss the idea with Lucy. After much painful fundraising we made Hackney Hear, a GPS locative audio app set in London’s poor yet rapidly gentrifying borough of Hackney.

We interviewed gang members, artists, and historians. We commissioned music, poetry, and short stories. We used Cardiff’s techniques throughout — as you walk through the park, you’d hear the voice of novelist Iain Sinclair invite you to sit on the bench you are approaching. You’d sit next to his invisible presence and he tells you about the area he loves and has lived in for decades. We used binaural “ghost” recordings throughout. You’d walk through a ghostly market being set up and then cleared away. In the park you dodged footballers and hoola-hoopers.

You could do all this without poking at your phone. At the beginning of the experience you were told to put your mobile in your pocket and explore. If you tried to walk out of the zone a voice would whisper at you to turn around.

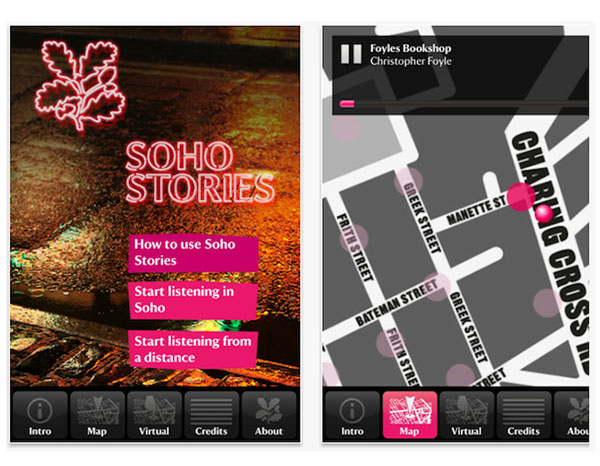

Lucy and I were hooked. We set up a company called Phantom Productions to make more sonic AR experiences, which we did — in Soho for the National Trust, in New Jersey about hurricane Sandy, another in Kings Cross for the Guardian.

We began to devise an approach as we learned what worked and what didn’t. In fact, our training as radio producers didn’t help much. We were used to describing scenes, which is not only irrelevant when you’re physically there, it’s downright annoying.

Others around the world were doing the same: in Berlin, the audio company Rimini Protokoll made a “Stasi audio walk” using archives; sound artist Halsey Burgund developed an open-source contributory audio AR platform called Roundware for his installations; and the British company Calvium built an interface to make it easy for producers to build their own experiences, allowing companies such as the Royal Shakespeare company to build their own apps. Musicians too were experimenting. RJDJ used the microphone on people’s phones to make music by live-processing the sounds.

For many years this work in locative audio chugged along quietly, minding its own business, waiting for its time to come.

This time appeared to be in 2015, when former Groupon founder and entrepreneur Andrew Mason poured his own money into the GPS audio walking tour company Detour. Unlike the artists and musicians before him, he had commercial ambition. He hired some of the best radio producers in the industry, and set about making highly-crafted documentary-style walks all around the world, partnering with companies such as Airbnb, RadioLab and SXSW. And he charged. At first, you could buy walks individually for $5 or $10. Later, this expanded to bundles of walks. You could sync your walk with your friends and do the walk in groups. The idea was that, in the end, the public would take over the platform and create their own Detours.

But Detour highlighted geo-located audio’s main disadvantage: reach. To experience Mason’s walks you had to be on location, and compared to the mass audience online this meant the potential audience was small. After three years, Detour closed. Mason has since turned his attention to Descript, the software system built for Detour which allows you to edit sound by working directly with the transcript.

It’s possible that Detour, like many of us, was just ahead of its time.

Right now, many of locative audio’s constituent parts are either fashionable or downright popular. Podcasting has finally taken off. Google and Amazon are investing in “Voice” — i.e., Siri, Alexa and that ilk. And if you pair these voice assistants with “hearables” (smart ear buds) you have the potential for augmented reality to take off.

Bose has serious ambitions for the Frames they have just launched. They are hearables in sunglasses form, but, in fact, the glasses part is a bit of a red herring. There is nothing visually augmented. They are just holders for little speakers which sit just above your ears but not over or in them, so you can hear the sounds of the real world around you too.

They also contain a small motor sensor (IMU) and bluetooth receiver, which means if synced with the Bose app on your phone, the combined system can track your GPS coordinates as well as your head movements. This means the locative audio can now, in theory, be accurate, specific, and three-dimensional—a far cry from the tech I was working with back in 2011.

Earlier this year, Bose announced a $50 million investment fund to support startups that are developing applications for the new platform. Currently, the company is branding Frames as “sunglasses with a soundtrack,” but the press release states that “music is just the beginning.” Coming soon will be a software update that includes applications for fitness, travel, and games.

Sennheiser also has an Immersive Audio program called AMBEO. However, the company seems to have little ambition to build in head-tracking or GPS capabilities. Instead, Sennheiser focuses on making 3D recording easy for anyone—for example, building binaural microphones into headsets so you can both listen and record. Sennheiser is also developing headsets which allow you to bleed in as much of the outside world as you want, especially for AR applications.

All in all, “Audio AR” seems to have gathered some momentum, and, compared to visual AR and VR, the technical barriers seem marginal. With the integration of the Voice technologies, you can imagine audio AR being used pretty easily, perhaps not as glasses but as sensor-equipped headphones or earbuds.

For makers, these technologies open up new creative possibilities. Head tracking means you can make dynamic spatialized audio. Whereas previously the sounds were “fixed” on your ears, now you can place your sounds in space around you.

And, for me, the development of “Audio AR” has resparked my enthusiasm for locative audio. I’m relistening to Janet Cardiff and again dreaming up projects which allow us as storytellers to intervene through audio in these spaces.

Walking is very calming, one step after another. One foot moving into the future, one in the past. Did you ever think about that? Like our bodies are caught in the middle. The hard past is being in the present. Really being here. Really feeling alive. — Janet Cardiff, Her Long Black Hair

Roundware Case Study

Roundware, a platform for audio augmented reality, immerses participants in geolocated soundscapes and invites them to add their own stories to the mix.

On a damp January day, I stand in front of one of Harvard Yard’s ornate wrought-iron gates. In the yard, snowdrifts are beginning to melt around the pathways, creating treacherous puddles of slush. Students and professors in peacoats and fleece jackets—and in one case, basketball shorts—stride purposefully between stately brick buildings. A large tour group, an omnipresent sight here, moves at a more leisurely pace. I take out my iPhone, put on my headphones, and open up the app that I’ve downloaded for this occasion. The start screen only has two buttons: “listen” and “speak.” I press “listen,” and begin to meander across the yard.

Slow, atmospheric music immediately begins to play. The soothing tones create a slight sense of distance—I feel like I have entered a separate, parallel Harvard Yard, a space of whispered intimacy at a remove from the bustle of campus life. As I pass an intersection, a man’s voice begins to speak in my ears. “I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox,” reads William Carlos Williams from his famous poem “This Is Just To Say.” His words drift off as I walk forward. A few moments later, I hear a man pensively speaking, as if to himself, in Arabic. After wandering for some time, I pause to explore the “speak” option, which invites me to record my own voice to add to this unruly collection and provides some prompts, like “Read some verses,” “Talk about a nearby gate,” and “Ask a question based on something you heard.” Back in “listen” mode, I find that I can also filter what I hear, based on these same prompts. Voices run together, overlapping, scattering, sometimes harmonizing serendipitously with the omnipresent music. The sensation of the soundscape responding to my bodily movement is an interesting one; I experiment a bit, pacing back and forth and feeling a bit self-conscious as I lean first one way and then the other. The responsiveness, minimal interface, and seamlessly blended sound combine to create a profoundly embodied and immersive experience.

This is re~verse, a participatory, location-based installation by sound artist Halsey Burgund, based on his platform Roundware. Created in collaboration with Harvard’s metaLAB and Woodberry Poetry Room, it features more than a thousand audio clips from Harvard’s collection of recorded poetry. This rich archive spans nearly a century and includes the first recordings of T.S. Eliot and Sylvia Plath, as well as readings by luminaries such as W. H. Auden, Anaïs Nin, Amiri Baraka, Ezra Pound, and Audre Lorde. re~verse brings these recordings out into the physical space of the campus, and invites students, poetry lovers, and passers-by to participate in an embodied exploration of poetry, space, and history, as well as to contribute their own voices to a murmuring, intricate, and constantly evolving tapestry.

Click here to listen to an audio clip from re~verse:

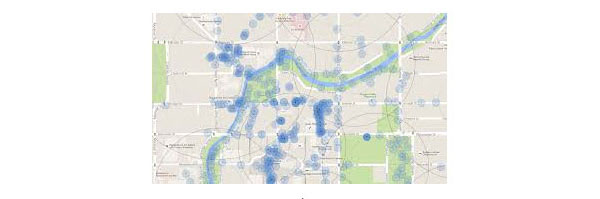

Contributory, Location-Based Audio

Developed by Burgund to facilitate his sound installations, Roundware is a contributory audio platform that allows creators to augment the physical landscape with location-aware layers of music and recorded voices. Using a mobile app and headphones, participants are immersed in a soundscape that responds dynamically to their location and movement. They can listen and wander, filter their audio stream in a number of ways, or record their own commentary to add to the project. Contributions are tagged with location information as well as project-specific metadata—for example, in re~verse, participants can self-identify as poetry lovers or neophytes. Gradually, user contributions build up across the landscape, documenting a multiplicity of voices and subjective experiences over time.

Burgund has used Roundware to create installations across the globe, from a cranberry bog in Massachusetts to World War I sites in northeast England to downtown Christchurch, New Zealand. He has also developed Roundware-based educational audio projects for the Smithsonian, UNESCO, and other cultural institutions, including projects focused on accessibility for the blind. The works range in their thematic focus, sometimes simply inviting participants to share a thought or experience, sometimes emphasizing topics like political discourse, local history, or poetry, as in re~verse. And while Roundware’s functionality supports the creation of contributory, location-based experiences, Burgund has also used it for browser-based audio projects and site-specific sound installations that are neither contributory nor location-aware. The platform lends itself to a host of different applications, and because it is open-source, even Burgund himself isn’t privy to all the different instances and modes in which it has been employed.

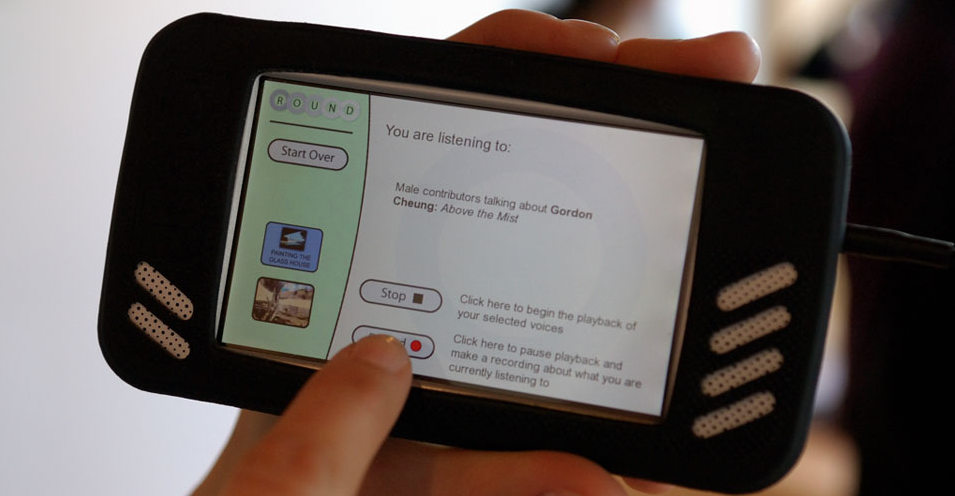

Project Genesis

Roundware began in 2007, as technical platform for Burgund’s ROUND installation at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. As a sound artist, Burgund has long been drawn to the human voice—its musical qualities, shades of emotion, and intimate reflection of the diversity of human experience. For ROUND, Burgund developed a tablet-based system (smart phones had not yet become mainstream, although they were poised to do so later that year) that invited museum visitors to contribute their thoughts about various works of art. While standing in front of a painting, viewers could listen to commentary by a curator, hear observations from previous visitors, and add their own opinions. “It all came out of my dislike of museum audio tours,” says Burgund. He wanted to democratize conversations about art, and disapproved of authoritative audio tours telling visitors what they were “supposed” to think.

This emphasis on openness and plurality is embedded deeply in the platform itself. Roundware’s website emphatically states, “Roundware is not audio tour software! In some ways, Roundware is the anti-audio tour platform.” It further explains the distinction:

- Audio tours are traditionally about a single authoritative voice whereas Roundware is about a multitude of voices, opinions and ideas mixed together.

- Audio tours tend to be linear experiences; Roundware is based on a non-linear, flexible, participant-driven, immersive experience.

- Roundware is designed for sculpting an aesthetic experience, not for explicitly delivering educational or interpretive information.

ROUND established both the platform’s core functionality—the ability to record audio, add recordings to a database, and play them back in a stream with specific parameters—and its core affordance, building contributory, location-based installations. Since 2007, Burgund has continued to develop Roundware in a heavily iterative process, regularly expanding its functionality in order to fulfill his own creative needs as well as specific requests from clients.

Functionality and User Experience

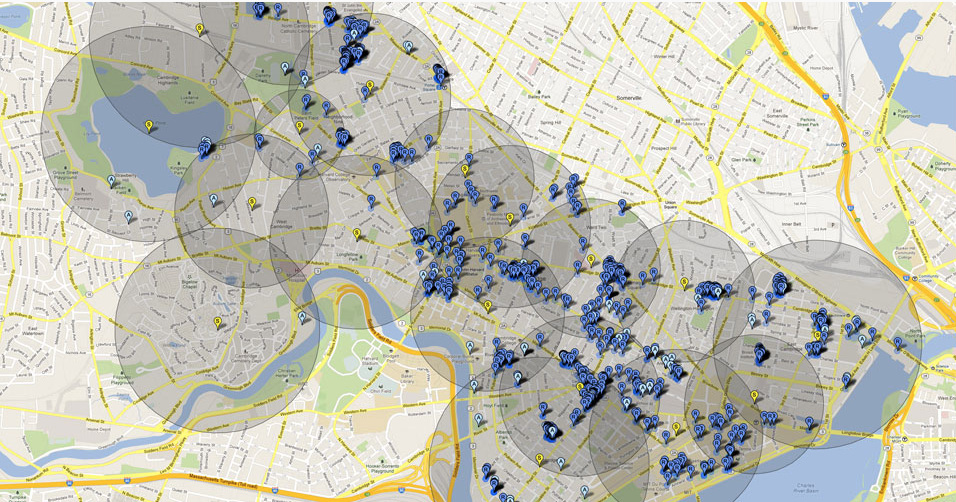

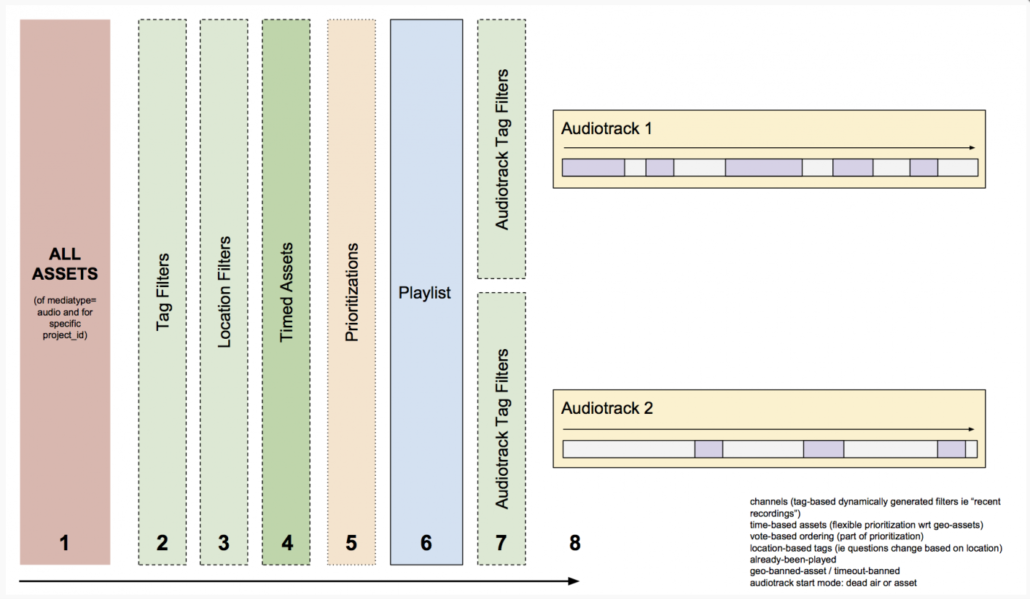

Roundware is a client-server system; clients for iOS, Android, and HTML5 browsers communicate with the Roundware server, which runs on Django, Apache, and Ubuntu Linux. Within this system, two basic categories of audio content are supported. A base layer of continuous audio, comprised of site-specific music composed by Burgund, is placed over the entire area of the project. Different tracks are each assigned to a relatively large geographic area—essentially, a polygon that he draws on a map. As a participant moves across these invisible shapes, they will hear their corresponding musical pieces, which collectively form the overall composition. The second layer of sound, the momentary layer, consists of intermittent audio clips—typically in Burgund’s work, these are voices, although any kind of audio can be used—that are shorter, non-looping, and assigned to a smaller area. Burgund adds some of this momentary audio to the initial soundscape, and over the course of the project, participants contribute additional snippets using the mobile app. As listeners wander around the project area, their physical location, as well as any filters they have selected, triggers nearby audio clips that play for a brief moment. It’s possible to simply have a silent base layer, but Halsey sees the music as an essential component of creating an overall environment, an ambience within which all the content lives. He says, “I think of the continuous layer as the ocean that the intermittent audio is swimming in.”

Beyond this basic two-layer structure, each installation is also shaped by an array of aesthetic and experiential considerations.For the momentary audio, each clip has a circular area of distribution, with a center point and a radius. Creators can control the size of the radius—for example, choosing a larger radius for larger geographic areas, so that participants are more likely to trigger the files. Once someone triggers a clip, it plays for a predetermined length of time, even if the user moves outside the file’s radius. This is an important part of the experience design: if clips stopped playing as soon as users exited their radius, the experience would largely consist of two- or three-second clips, which would be unsatisfying and would not allow users to substantively engage with the content. How long the clips play once participants move outside their radius can be tailored to the needs of specific projects. An algorithm also ensures that visitors don’t hear the same clips repeated during their experience. Burgund makes the case that these details are crucial to both Roundware and the type of work that it supports:

Roundware has a whole lot of parameters that would not be there if somebody designed it for advertising. I think that its artistic roots are very clear in that sense. […] This is all the aesthetic stuff. This is how long the recordings are, or how long this dead space air is between. This is how it fades out. This is how it pans back and forth. Those things are really important.

This careful attention to participatory aesthetics is crucial to the success of both participatory documentary and location-based works.

While Roundware provides creators with a great deal of specificity, projects created on the platform also inherently include elements of chance and randomization. Participants walking the same route in an installation will not hear precisely the same things; Burgund says, “It would be almost impossible to recreate the exact same experience.” In each installation there are areas of high density, where many audio clips have been added—perhaps near a bench where people can pause for a moment, or a landmark that invites exploration. In these areas, creators can limit how many files will play at once—Burgund usually limits it to two at a time—so that the overlaid clips do not simply become incomprehensible noise. Within that restriction, the length of each clip is different, and the ordering of the clips is randomized. Moreover, there are what Burgund calls “systemic randomizations,” small variations due to GPS’s imperfect accuracy, or the fluctuating strength of a wi-fi signal. And of course, most visitors’ paths will be unique in some way: how fast they walk, where they decide to pause, whether they choose to retrace their steps. Thus, Roundware offers an experience that is at all times a dialogue between creators, participants, and the dynamic conditions of the physical and virtual environment around them.

Contributory Ethos and Collective Storytelling

If you tell your participants you don’t trust them, then they’re going to do stupid things. If you tell them you trust them, you give them good examples, you encourage them in the right way, then generally they’ll do something that’s respectful and consistent with the ethos of the piece.

Roundware was conceived from the very beginning as a contributory platform—the capacity for users to add their own content was central to its functionality and ethos from the start. Burgund stresses the distinction between contributory and interactive projects: regarding the latter, he feels they often seek solely to create an ephemeral individual experience, one whose novelty fades quickly away and which has no effect on other participants. In contrast, in a contributory project, “You’re contributing to a larger whole, leaving something of yourself for others, co-creating something such that future participants are affected by past contributions.” (He finds “participatory” to be a more nebulous umbrella term, used to describe both interactive and contributory works.) Roundware contributions are uploaded automatically and immediately added to the piece, with no approval period. Burgund believes this is crucial to encouraging constructive and thoughtful discourse, saying:

He does listen to the recordings after they have been uploaded, primarily because he is interested in hearing what people have contributed. Out of thousands of contributions, he says he has only had to remove offensive content—what he describes as hate speech—once or twice. The only other oversight he exercises is modulating the volume of loud screams so that they do not cause physical discomfort to listeners. This openness and immediacy produces an environment that encourages participants to playfully experiment with creative modes of collective storytelling.

One day in 2010, Burgund checked on the new additions to his Scapes installation at the deCordova Sculpture Park. A teenager had recorded a frantic, whispered message: “I’m behind this sculpture. I’m trying to hide from these zombies that are walking around. Wish me luck.” Amused, he thought nothing more of it. Then, a few days later, a new recording showed up in the same area of the park: “I was just by that rock over there, and there was a dead body and a zombie was eating its brains.” From there, the story continued to unfold over the next four months, with the beleaguered survivors finally being airlifted out by helicopter.

Beyond its creativity and the entertaining arc of its narrative, what was extraordinary about this zombie epic was the fact that so many different people—most of them children—had contributed to this story, all visiting the installation independently at different times. With no prompting beyond hearing a snippet of the story during their visit to the park, they enthusiastically joined in this collective storytelling effort. Roundware’s dynamic soundscapes augment the physical landscape with a new layer of collaborative creativity and social interaction; Burgund also points to other examples in which people left spatially oriented instructions for future visitors, creating treasure hunt-like experiences.

Watch a short video about Scapes:

<[…] a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve playful-constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll. In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.2

Authorship and User Agency

Burgund conceptualizes his authorship in these works as “framework building […] I create this framework, which is technical and conceptual and aesthetic, and then I just open it up for people to come in.” He views his work as a collaboration between the participants and himself, and enjoys that the results are not fully under his control: between the algorithmic randomization of Roundware and the systems supporting it, the ever-changing conditions of the physical space of the work, and the diverse ways in which participants engage with and contribute to the experience, the results of this collaboration often surprise Burgund and inspire new directions for artistic and technological exploration.

At the same time, he shapes users’ experiences and contributions, “nudging” them to participate in the piece, via his decisions about spatial layout and user interface. And while users certainly play an essential role in each project, authoring much of the content, their agency is ultimately quite restricted. For example, they do not have the ability to select a particular item and play it when they want to hear it, and the user interface provides no information about what content is located where. Both artist and participants must accept a lack of total control over the experience. Burgund says that the limited user agency is on purpose: “I don’t want people to have to make a decision that they’re not equipped to make.” He feels that viewers, when presented with a selection of media content without much context, often choose arbitrarily. By taking this choice away, he hopes to simplify the user experience as well as counter subconscious biases and behavioral patterns.

Burgund uses the open-source software term BDFL, or “Benevolent Dictator for Life,” to describe his role managing the Roundware code: while it is open-source, he decides what is ultimately added to the core code, guides its overall development, and enforces aesthetic standards. Arguably, BDFL also applies to Burgund’s stewardship of the overall Roundware experience. Although Roundware installations are collectively created via user contributions, Burgund remains the singular artist gathering and shaping these inputs into a work that represents his artistic vision.

Non-linear Exploration

In contrast to linear spatial narratives that physically and figuratively bring participants from one point to another, like audio tours with a set of specific stops (often linearly arranged), Burgund says, “Roundware is just an area that’s been activated, where you’re tuning in to this evolving audio stream. It’s like a radio.” There is no explicit narrative structure that guides viewers from place to place.1 Their path is determined by their own whims and curiosity, as well as each space’s unique and dynamic characteristics—from landmarks to weather to the flow of people through a location.

This nonlinear mode of exploration evokes the dérive (taken literally, “drift” or “drifting”), a concept formulated by French theorist Guy Debord. Debord was a founding member of the Situationists, an avant-garde collective of activist artists who envisioned subversively playful practices to counter the alienation, rationalization, and predictable hierarchy of modern cities. Debord described the dérive thusly:

[…] a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve playful-constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll. In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.2

The notions of fluid movement, immersion in ambience, and attentive participation in an environment are all reflected in the Roundware experience. Each installation’s multiplicity of voices, running together and speaking over each other, also resonates with the Situationist project of destabilizing singular, authoritative narratives of public space.

Layers and Temporality

Beyond the digital layering of the voices themselves, Roundware also exists as an invisible virtual layer on top of a physical place, inviting participants to consider a pluralized sense of place and the complex relationships between location, the physical, and the virtual. Each installation itself is composed of a multitude of temporal layers. Often, the initial content is already temporally layered—as with projects like re~verse in which Burgund juxtaposes historical recordings from different periods with contemporary music. Regardless, over time, all Roundware experiences build up intricate layers of media content, as participants add to each installation throughout the duration of its existence. These recordings remain tethered to the specific spot in which they were made, so participants in any one location encounter a dynamic mixture of all of the thoughts and experiences that previous visitors shared at that spot. The often densely layered fragments, sometimes spanning centuries, become compressed into the present experience of each participant.

At the same time, user recordings join a documentary archive, but one with almost no curation, moderation, or requirements for inclusion. Rather than looking backward to collect documents of importance, Roundware creates an archive of the present that is both virtual and, through its geolocation, profoundly physical. In doing so, it offers a conception of space as a temporal process, and asks participants to reexamine commonly held notions of history, memory, and documentation.

Archaeologist Michael Shanks’ writing on the deep map (a term coined by William Least Heat-Moon in his 1991 book PrairyErth) is helpful in understanding the ways in which past, present, and future spatialities can intersect:

[…] The deep map attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place through juxtapositions and interpenetrations of the historical and the contemporary, the political and the poetic, the discursive and the sensual, the conflation of oral testimony, anthology, memoir, biography, natural history and everything you might ever want to say about a place.3

Deep mapping counters simplistic binaries between past and present, public and private, objective and subjective. It defamiliarizes our everyday surroundings in order to highlight overlooked features and interconnections, reflecting “the palimpsest that is landscape – the percolating time that folds together the many fragmentary traces of pasts present in any one place.”4

Audio Augmented Reality

Burgund conceptualizes Roundware as audio augmented reality: “I’ve always thought of it that way. It augments the physical landscape with a layer of audio. But I’ve only recently taken to describing it that way, because people now know a little more about what that is.” Audio AR is inherently location-based, with audio files triggered based on a user’s location. It is already being used for a plethora of applications, including gaming, immersive theater, navigation, tourism, and accessibility for the visually impaired. However, mainstream industry discourse around AR remains overwhelmingly focused on head-mounted displays.

Audio AR’s lack of visibility (pardon the pun) is partially due to the same terminological confusion that plagues both location-based media and augmented reality. The concept of audio that augments the physical world through location-based content has been variously described as dynamic spatial audio, ambient spatial audio, location-based audio, location-aware audio, and geotagged audio, among other terms. Despite this lexical difficulty, audio AR has unique affordances that underscore some of the limitations of visual AR.

Burgund argues that visual AR puts a camera between users and the world, “reducing the world to the part that fits into the margins of your screen.” By pulling users’ attention to a screen rather than the world around them, visual AR often prioritizes the augmentation itself, rather than the reality it augments. Many AR demos, for example, emphasize a scientific model or whimsical character, rather than the space users are in, or their interactions with surrounding people. A key affordance of both location-based media and AR is that they are able to build on, and interact with, the most engaging characteristics of the physical environment they are situated in: from historical details to natural scenery to electronic displays. This potential risks being diminished in camera- and headset-mediated experiences. Burgund says, “I think it is crucial for the people designing these systems to think about this and do what they can to really augment rather than mask reality.”

Roundware also invites reflection on embodied interaction and user interface in AR. Roundware installations require relatively little interaction via the mobile app, with the exception of recording audio contributions. For the most part, bodily movement is the primary user interface. “My motto has always been, ‘Press play and put it in your pocket.’ Then you’re just walking,” says Burgund. For AR, it is neither feasible nor desirable to have bulky, elaborate interfaces—in terms of both simplifying user experience and not distracting users from the environment around them. Most manufacturers of head-mounted displays are already working with gestural interfaces, in which users interact with computing systems through hand motions (or other bodily motions). Ideally, this creates a more intuitive and immersive experience by seamlessly linking digital devices with the physical world. Rus Gant, Director of Harvard’s Visualization Research and Teaching Laboratory, notes that audio AR represents an underexplored but crucial aspect of conceptualizing how AR can and will function on a material level. Speaking about Apple’s new Bluetooth earbuds, he says:

[People] think they’re just headphones. No, this is much more specific. This knows where your head is looking, knows where your head is in geographic space. The headphone knows that. It can check with the phone: ‘Where are we? Now we’re over here.’ And then it can check with the cloud: ‘Did we do this last week at the same time and the same place?’

Gant argues that these earbuds, in combination with a smartphone and other linked devices like smart watches (and eventually, head-mounted displays), constitute a “body-centric ecosystem” that will redefine approaches to AR.

Access and Activism in Roundware’s Future

Roundware was designed with access as a key principle. Burgund is passionate about creating art outside of traditional white cube art spaces: as an artist, he draws on the inspiration of being in everyday spaces where people live, work, and play. He also wants his work to be accessible to a broader, more diverse audience, rather than “behind the gates of some art museum where there’s either a pay wall, or a class wall, or a socioeconomic wall, purposeful or not.” Roundware is also open source, for two primary reasons. Firstly, Roundware depends on open source software to operate (including Apache, Ubuntu, and Django), so Burgund feels it is important to give back to the community. Secondly and perhaps most importantly, he says:

The whole philosophy behind Roundware of collectively creating something greater than any single contributor over time, piece by piece, is shared with the open source, social coding community. It feels wrong to have a platform that enables work that depends on community contributions be itself closed off and proprietary.

Although Roundware is open source, Burgund acknowledges that it would be difficult for someone without prior programming experience to set up their own installation. And of course, most of his projects require a mobile phone, another barrier to entry. One of his main goals for the platform going forward is to make it more user-friendly and accessible—this includes bringing Roundware into schools as a learning tool, as well as developing better methods for publicizing installations that are otherwise invisible.

One of Roundware’s most intriguing potential applications is for activist-oriented projects. The platform’s onsite documentation and archival capabilities could serve as important tools for activist movements, which are often oriented around specific events and locations. In 2015, Burgund and Egyptian-Lebanese artist Lara Baladi created the Roundware installation Invisible Monument, located in Boston’s Dewey Square—the main site of Occupy Boston. Although onsite documentation wasn’t possible in this case (the protests took place in fall 2011), Baladi and Burgund gathered recordings made during that time period, and used them to recreate a soundscape of the protest. In the future, demonstrations and other events could be both recorded and preserved on-site, creating a ground-level archive of participants’ experiences. This possibility suggests important questions about physical and virtual public space: when protests are shut down and activists are forcibly removed from parks and streets, what does it mean that a virtual record of the protesters could live on in that same space? By geolocating digital media, how can location-based projects intervene in our understanding of free speech and public space? Burgund points out that, since Roundware requires no hardware onsite, “I can do a Roundware installation without any permission. I could put a Roundware installation inside of the Pentagon and nobody would listen to it, but it would be there.”

Conclusion

Roundware is already an incredibly versatile and conceptually rich platform: an artistic and documentary tool for realizing site-specific soundscapes; an asynchronous, location-based social network for collective storytelling; a narrative platform supporting experimentation with linearity and temporality; and an example of audio AR that invites us to re-think AR content and user interfaces. Users are immersed in enchanted landscapes that invite spontaneous interactions, playful discovery, and creative contribution. Roundware’s adaptability for civic interventions, and the potential for it to be more widely accessible for both participation and creation, are only two of many exciting avenues for future technological and artistic experimentation.

Notes:

1. Recently, Burgund introduced the capacity to add time-based assets to Roundware installations; this new feature introduces the possibility of introducing a structured narrative arc into the experience.

2. Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. and trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 62.

3. Michael Shanks and Mike Pearson, Theatre/Archaeology (New York: Routledge, 2001): 64-65.

4. Jeffrey Schnapp, Michael Shanks, and Matthew Tiews, “Archaeology, Modernism, Modernity,” Modernism/Modernity vol. 11, no. 1 (2004): 11.

Additional References:

Halsey Burgund, interviewed by author, 2016-2017.

Rus Gant, interviewed by author, 2017.

This article was written for and originally published on Docubase from the MIT Open Documentary Lab. It is cross-posted here with permission and much appreciation.

Sound That Surrounds, A Reflection on Immersive Audio in Three Movements

Sound often plays second-fiddle in discussions about emerging media forms. But what happens when makers build experiences around it? In this dialogue, three fellows at MIT’s Open Doc Lab share insights about their current projects, how they build relationships between audio and the world that listeners are passing through, and the role of participation in their work.

Each of them has also provided “field notes” with more details on their projects. Learn more about Pan-terrestrial People’s Anthem, a project that combines compositions and poetry by Andrew Demirjian; an audio journey through the Anthropocene titled From Here to Where by Halsey Burgund, and A Father’s Lullaby by Rashin Fahandej, which cross-examines poetic and spatial justice using site-responsive public installations.

MOVEMENT I: Creation

> Jump to Movement II: Location or Movement III: Participation

Demirjian: Let’s start by talking about “immersion.” What does this mean in your work?

Burgund: I think about From Here to Where as a sort of dual immersion because you’re listening in a car and the car provides this little audio bubble, where you and your companions are all hearing the same stuff. But then there’s this skin that separates you from the outside. (Listen here)

So, you are immersed in this audio bubble traveling through an expansive visual landscape that you are also immersed in and connected to. These two layers of immersion — one audio and proximal and the other visual and expansive — are connected to each other along the entire journey.

This feels different to me than the VR type of immersion, which takes you away from the real world. I tend to be a fan of the kind of immersion which connects you to what’s around you. You’re looking at stuff, you’re smelling things, you’re feeling the wind, you’re experiencing the natural world. Then that’s augmented by this extra layer of audio which is not “real” in the sense that it’s not being generated by physical objects that are in your proximity but has been carefully designed to bring you closer to your physical environment.

Using an augmentation to connect rather than to segregate is something that I think a lot about, although there are challenges because the technology always ends up mediating in some way that pulls you away from the analog world.

The necessity to use the technology is something that I get frustrated with sometimes. It’s a double-edged sword that enables you to do these things but then piles requirement upon requirement onto you and your public, your listeners, your experiencers.

I try to just make it disappear — press play and then put your phone away — but even that is far from ideal. I would much prefer it if you could just walk naked through the environment with no technology whatsoever and experience the piece! I feel like that’s the ultimate level of accessibility. I think a lot about accessibility both in terms of socioeconomic accessibility and physical accessibility. Universal design is a high ideal but one that I find useful to consider throughout the creative process.

Demirjian: Rashin, Halsey says that he likes to use augmentation to connect people to nature, to their surroundings. In my piece, I’m using music to disconnect people from their belief systems related to the nation-state. Do you feel you are using sound to connect or disconnect listeners?

Fahandej: I am interested in the use of technology to bring attention back to our bodies, and intentionality to our actions — a kind of immersion that does not start and end with technology like a VR headset, which takes you away from your surroundings.

The experience at the installation site for A Father’s Lullaby is an encounter with the unexpected: the sound of lullabies sung by men coming from treetops across the public plaza. The melodies move with you in the space and persist in a subtle way, while fading in and out as you move through multiple sources of sound.

I am interested in using technology to create a new social memory of space. And the public space allows for accessibility and diverse voices to co-exist. Similar to Halsey, I try to create an immersion to give you pause and make you aware of your surroundings, blurring the boundaries of real and imagined.

My projects deal with social issues, constructs and systems. In this particular piece, I ask people to participate by thinking about memories of their childhood, tender relationships of love, and then to sing and record a lullaby. The project is about racial disparities in the system of incarceration in the United States, the absence of many fathers as a result, and the impact of that on children, women, and lower-income communities. The entry point is recalling our own deep personal experiences in order to connect us with a broader socio-political issue.

Similar to your project, Andrew, it invites audience members to disconnect from an established social belief system.

Demirjian: You’re thinking about making new spaces, new memories that you want to see. This is like making a new anthem for a future you want to see. How can sound be used to make a future memory or create an aspirational place?

Burgund: Andrew, you were talking earlier about wanting to in some ways disentangle your listener’s sense of connection to or dependence on feelings of nationalism.

It was interesting to listen to your pieces because there is obviously a huge entanglement in the creation of the piece since you’re taking audio snippets from different anthems and bringing them together. In some places, you are weaving together regal sounds of horns and drums and it all sounds very anthemic. But then there’s a voice piece that is so spooky!

That one is so haunting, so beautiful. The breathiness and close-miking is very personal and intimate. You can feel yourself right there with the singer. I don’t know if you sped that up or slowed it down, but the effect was really amazing. It connected me to that individual singer, and it connected me to all the other people out there who feel connected to their country, their heritage.

What’s fascinating about your piece is the two sides, the connecting and disconnecting at the same time.

Demirjian: It is so great to hear you talking about Ami Yamazaki’s vocal performance. When I present this work in talks it’s not a piece I tend to play because it’s so intimate. There’s something about listening to this with headphones on that makes it such a moving experience.

How do you create an anthem that emphasizes interdependence and not exclusion?

Burgund: What country was that?

Demirjian: Ami is singing her interpretation of one of the snowball poems in a book made from a bunch of national anthems. I’m not doing any time stretching, there is only a little delay and reverb. She was riffing on the phonemes and language of the constituent parts of the words in the lyrics. She was deconstructing them and pulling them apart and compressing the fragments together. It is her performance of a poem.

Burgund: So you’re like double remixing. You’re mixing the lyrics and she is remixing the remix and you’re mixing them again.

I don’t know national anthems other than my own. To what extent do you think that matters to experience your piece? Does being able to pick out a bit of the Latvian anthem and juxtapose that with the Hungarian anthem enhance the experience by creating some sort of intellectual connection between those countries?

Demirjian: I think what matters is knowing that it’s a remix of all national anthems; it’s not necessary for people to have a wide range of knowledge. It could be more like a kind of game to see if they can identify the source. It could add a different level…

Burgund: Rashin, you were born in Iran and grew up and spent a lot of your life over there before coming to America. How do you feel when you listen to something like this?

Fahandej: National anthems are a genre that I have little regard for. I’ve seen very thin lines between patriotism and aggression against those whom we consider others. They have been used to rage wars, to oppress and to exploit in the name of borderline and patriotism. The reexamination of the anthems to break their rigid boundaries and to redefine them gives them a beautiful poetry in Andrew’s piece.

Demirjian: What I was trying to get at with this piece is that the old way of thinking about nations as separate and competing for resources has to be changed. How do you create an anthem that emphasizes interdependence and not exclusion?

MOVEMENT II: LOCATION

> Jump to Movement I: Creation or Movement III: Participation

Demirjian: I want to ask you both about your process for composing for unique spatial situations. What was your process?

Fahandej: Creating sound for a public site is a vastly different process and outcome than a gallery setting, where variables are predictable. At a public site, uncontrollable elements will swing elbow-to-elbow with the artwork, shifting and changing the experience with every nudge. This co-presence and the emergence of artsound in public sites is at the core of A Father’s Lullaby.

There are two layers of sounds demanding different kinds of action and interaction. The sound of lullabies and singing projected from tree tops from multiple hubs across the public plaza can be heard if you are a passerby. If you come closer, your body triggers motion sensors connected to speakers in the raised garden level. The stories are fragmented portraits, audio documentaries of fathers on federal probation. This is the part that is not about transcendence but about attentive, active witnessing.

Soft voices find their way in the crowded noises of street corners, as if someone is calling you, singing for you. You have to be close to the sound source to hear the voices, and your next movement in the space triggers the next part of the story and memories to unfold. The experience for the listener happens in the form of discovery.

I am very curious about how these moments change and reshape our relationship to a particular public site. Even individual experiences can create a collective social memory of a site, and therefore create a shared experience that we carry with ourselves. Fathers told me that when they sing for their kids at home they think of this piece. A woman told me she called her elderly father after spending time at the installation site.