Sonifying the World: Has “Audio AR” finally found its moment?

Audio affects our perception of the physical world. We understand three-dimensional space by using our vision but also by the character of sounds we hear. If these sounds are manipulated and changed, then our perception of reality can be drastically affected. —Janet Cardiff

I became interested in audio AR almost a decade ago, before “augmented reality” had become an everyday term. In fact, back then we couldn’t quite agree on a term. Some used “locative audio.” I used “GPS location-based apps.” None were very snappy. In essence, what we all meant was layering audio in space. And it appealed to me because it had the potential to change our relationship with the real world around us.

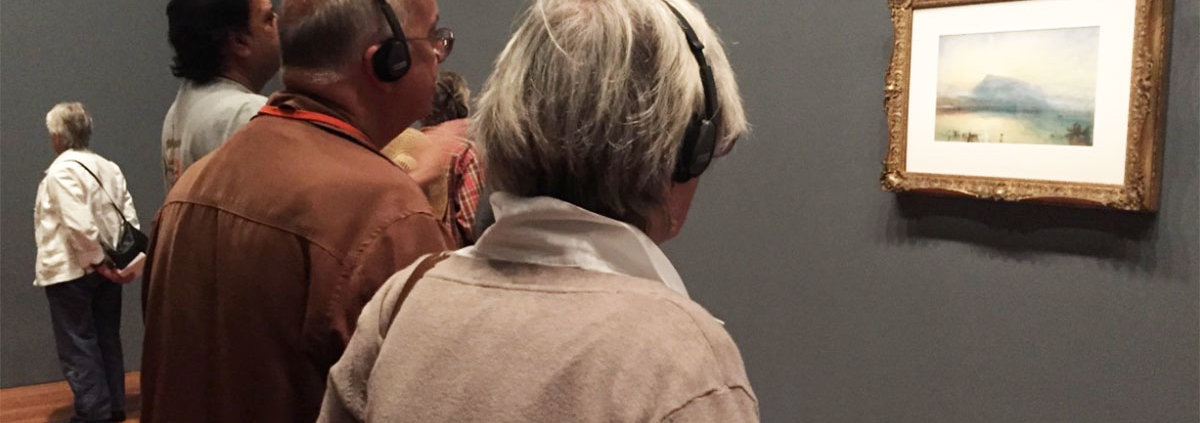

To explain this grand claim, let’s go right back to basics. Take, for example, tour guides. They tell you about the new city you are visiting, which changes the way you understand and relate to that place. Museum audio-guides do the same thing. By learning about the painting you are looking at, you begin to appreciate different things, to understand the work in a new way.

Artist Janet Cardiff understood this power of “audio AR.” Back in the 1990s, she built a number of audio walks. The technology was basic. To hear The Missing Voice, you needed to check out a Walkman at London’s Whitechapel Library. To keep in sync with the piece you’d have to walk in time with her:

By overlaying narrative in space, you can imbue that place with meaning, augmenting the world.

I want you to walk with me… Try to walk to the sound of my footsteps so that we can stay together.

Despite the crude tech, Cardiff seems to have instinctively understood some of the most powerful spatial storytelling techniques. Like a tour guide, Cardiff talks directly to you, pointing out details as you travel with her, highlighting the things you walk past every day, making you zoom in on them, but poetically, interweaving them in her noir-like plots.

I hope we see an egret. Yesterday I saw two flying over the lake, their big white wings floating above the water as they circled and then landed on the other side.

Cardiff also directs our attention through the use of field recordings. Using the hyper-real binaural recording technique (which places microphones beside your ears), she brings sounds in and out of focus. An invisible car swerves past you, sirens, horse clopping around you, an accordion players. You turn around to avoid them and see nothing there.

It’s loud here, isn’t it? When you are in a city like New York you have to think of the sounds like they are a symphony, otherwise you go a bit crazy.

As Steven Poole, my colleague at the Guardian, wrote of Cardiff’s work, “You experience two realities at once. And you can begin to play this game afterwards, imagining that the apparently random street scenes around you are carefully choreographed and soundtracked to a mysterious design.”

Back in 2010, though, I wasn’t thinking about these clever storytelling techniques. I was thinking about technology. I’ve never been a good sleeper, and sometime ideas keep me up. One night it was locative audio. I had been making a series of downloadable walking tours with my radio producer friend Lucy Greenwell, and, at about 4 a.m., I had a realisation that with smartphones and GPS all the painstaking timing and clicking and pausing could stop. The phones could trigger the audio files by your location. But it wasn’t only the timing, the walks could also be nonlinear — you could make audio experiences where people could roam free.

I convened an emergency lunchtime meeting near the Guardian at the local Italian deli to discuss the idea with Lucy. After much painful fundraising we made Hackney Hear, a GPS locative audio app set in London’s poor yet rapidly gentrifying borough of Hackney.

We interviewed gang members, artists, and historians. We commissioned music, poetry, and short stories. We used Cardiff’s techniques throughout — as you walk through the park, you’d hear the voice of novelist Iain Sinclair invite you to sit on the bench you are approaching. You’d sit next to his invisible presence and he tells you about the area he loves and has lived in for decades. We used binaural “ghost” recordings throughout. You’d walk through a ghostly market being set up and then cleared away. In the park you dodged footballers and hoola-hoopers.

You could do all this without poking at your phone. At the beginning of the experience you were told to put your mobile in your pocket and explore. If you tried to walk out of the zone a voice would whisper at you to turn around.

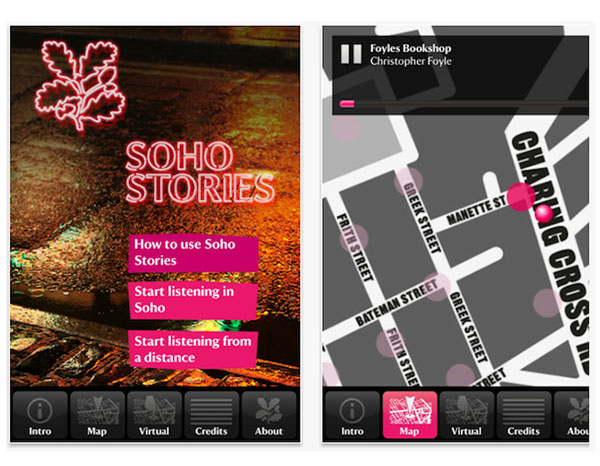

Lucy and I were hooked. We set up a company called Phantom Productions to make more sonic AR experiences, which we did — in Soho for the National Trust, in New Jersey about hurricane Sandy, another in Kings Cross for the Guardian.

We began to devise an approach as we learned what worked and what didn’t. In fact, our training as radio producers didn’t help much. We were used to describing scenes, which is not only irrelevant when you’re physically there, it’s downright annoying.

Others around the world were doing the same: in Berlin, the audio company Rimini Protokoll made a “Stasi audio walk” using archives; sound artist Halsey Burgund developed an open-source contributory audio AR platform called Roundware for his installations; and the British company Calvium built an interface to make it easy for producers to build their own experiences, allowing companies such as the Royal Shakespeare company to build their own apps. Musicians too were experimenting. RJDJ used the microphone on people’s phones to make music by live-processing the sounds.

For many years this work in locative audio chugged along quietly, minding its own business, waiting for its time to come.

This time appeared to be in 2015, when former Groupon founder and entrepreneur Andrew Mason poured his own money into the GPS audio walking tour company Detour. Unlike the artists and musicians before him, he had commercial ambition. He hired some of the best radio producers in the industry, and set about making highly-crafted documentary-style walks all around the world, partnering with companies such as Airbnb, RadioLab and SXSW. And he charged. At first, you could buy walks individually for $5 or $10. Later, this expanded to bundles of walks. You could sync your walk with your friends and do the walk in groups. The idea was that, in the end, the public would take over the platform and create their own Detours.

But Detour highlighted geo-located audio’s main disadvantage: reach. To experience Mason’s walks you had to be on location, and compared to the mass audience online this meant the potential audience was small. After three years, Detour closed. Mason has since turned his attention to Descript, the software system built for Detour which allows you to edit sound by working directly with the transcript.

It’s possible that Detour, like many of us, was just ahead of its time.

Right now, many of locative audio’s constituent parts are either fashionable or downright popular. Podcasting has finally taken off. Google and Amazon are investing in “Voice” — i.e., Siri, Alexa and that ilk. And if you pair these voice assistants with “hearables” (smart ear buds) you have the potential for augmented reality to take off.

Bose has serious ambitions for the Frames they have just launched. They are hearables in sunglasses form, but, in fact, the glasses part is a bit of a red herring. There is nothing visually augmented. They are just holders for little speakers which sit just above your ears but not over or in them, so you can hear the sounds of the real world around you too.

They also contain a small motor sensor (IMU) and bluetooth receiver, which means if synced with the Bose app on your phone, the combined system can track your GPS coordinates as well as your head movements. This means the locative audio can now, in theory, be accurate, specific, and three-dimensional—a far cry from the tech I was working with back in 2011.

Earlier this year, Bose announced a $50 million investment fund to support startups that are developing applications for the new platform. Currently, the company is branding Frames as “sunglasses with a soundtrack,” but the press release states that “music is just the beginning.” Coming soon will be a software update that includes applications for fitness, travel, and games.

Sennheiser also has an Immersive Audio program called AMBEO. However, the company seems to have little ambition to build in head-tracking or GPS capabilities. Instead, Sennheiser focuses on making 3D recording easy for anyone—for example, building binaural microphones into headsets so you can both listen and record. Sennheiser is also developing headsets which allow you to bleed in as much of the outside world as you want, especially for AR applications.

All in all, “Audio AR” seems to have gathered some momentum, and, compared to visual AR and VR, the technical barriers seem marginal. With the integration of the Voice technologies, you can imagine audio AR being used pretty easily, perhaps not as glasses but as sensor-equipped headphones or earbuds.

For makers, these technologies open up new creative possibilities. Head tracking means you can make dynamic spatialized audio. Whereas previously the sounds were “fixed” on your ears, now you can place your sounds in space around you.

And, for me, the development of “Audio AR” has resparked my enthusiasm for locative audio. I’m relistening to Janet Cardiff and again dreaming up projects which allow us as storytellers to intervene through audio in these spaces.

Walking is very calming, one step after another. One foot moving into the future, one in the past. Did you ever think about that? Like our bodies are caught in the middle. The hard past is being in the present. Really being here. Really feeling alive. — Janet Cardiff, Her Long Black Hair