top-level category for Blog posts

Interview with Ben Valentine

I interviewed Ben Valentine, Exhibition and Program Coordinator for Exhibit Columbus, about Exhibit Columbus, an extraordinary celebration of modernist and contemporary architecture that I had a chance to experience this year. Exhibit Columbus included an audio AR piece to complement the wide array of physical components and I wanted to share why they made this non-obvious design choice.

We often take the sounds of a city as a given—but they are there by design, whether thoughtful design or not.

What is Exhibit Columbus?

Exhibit Columbus is the flagship program of Landmark Columbus Foundation, whose mission is to care for the design heritage of Columbus, Indiana, USA and inspire communities to invest in architecture, art, and design to improve people’s lives and make cities better places to live. Exhibit Columbus is an annual exploration of architecture, art, design, and community that alternates between symposium and exhibition programming each year, and features the J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize.

What do you as organizers hope that visitors to Exhibit Columbus will gain/learn/remember?

We hope that visitors of any background recognize the value of good design in their lives, and see that the community is an integral aspect of that process. Thousands of people visit Columbus for its design heritage, and we want those visitors and locals alike to know that this unique legacy is alive and still transforming the city to this day.

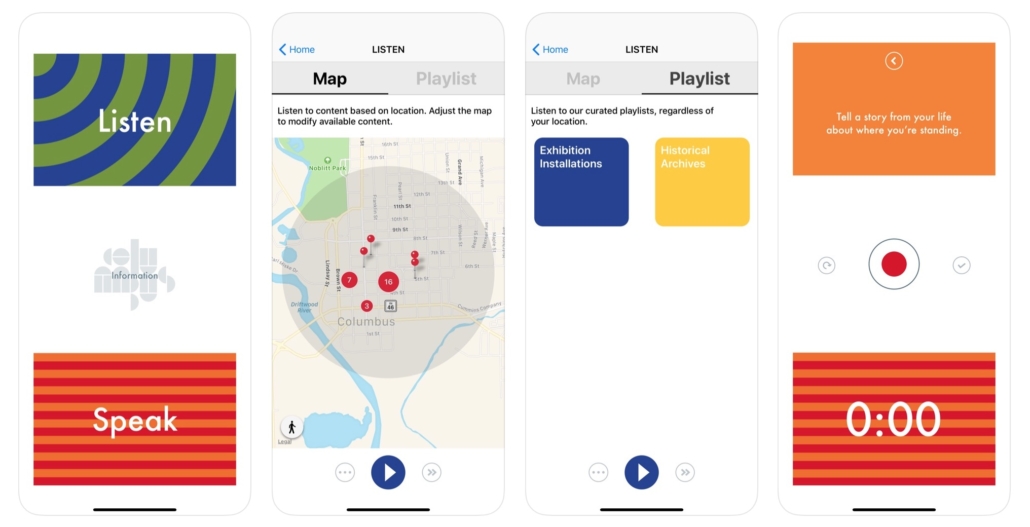

What is the Hear/Here app?

Hear/Here is an interactive location-based audio app that offers an aural exploration of the exhibition and invites visitors to upload their own voices to be shared with other visitors on-site. Historic audio clips, insights from community members, and interviews with exhibition participants come together in the Hear/Here app—creating a new way to interact with the exhibition and experience the city’s design legacy.

Historic audio clips, insights from community members, and interviews with exhibition participants come together in the Hear/Here app—creating a new way to interact with the exhibition and experience the city’s design legacy.

Why did you want the exhibition to include an audio AR component?

Exhibit Columbus wants to provide an enjoyable and meaningful experience for all ages and backgrounds. To do this, we wanted to create multiple ways to enter and experience the exhibition. Simply having the work in public is not enough. We provide a free Exhibition Guide that is written by our team and designed by Rick Valicenti of Thirst, but we also provide a Family Activity Guide, which this year was designed by Rosten Woo. Each one of these “guides” provides a different experience and entry point to the exhibition and opens up the city and the exhibition to many audiences.

I feel that augmented reality with solely audio, as opposed to more visual didactics, offers a great way to ingest additional context-specific information without getting too much in the way of the excellent architecture that our visitors are looking for.

Since architecture is so much about space, I feel that offering a location-specific experience throughout the streets of Columbus, not only where the exhibition installations are located and at the most famous buildings, but also in the interstitial spaces between them, makes a lot of sense and is very exciting. I feel that augmented reality with solely audio, as opposed to more visual didactics, offers a great way to ingest additional context-specific information without getting too much in the way of the excellent architecture that our visitors are looking for.

How can audio and architecture interact? Are there any specific examples related to Exhibit Columbus pieces?

Architecture is created and molded by those who desire it, fund it, and occupy its space. It is never a static object empty of context. The Hear/Here app allows us the opportunity to insert voices and ideas that were integral to the architecture that defines Columbus, as well as the new installations of our exhibition. It humanizes and contextualizes the forms, allowing them to speak and share with the audience in a new way.

For instance, when you stand in front of I.M. Pei’s Cleo Rogers Memorial Library, you hear I.M. Pei discussing its design and you hear the former Mayor discuss the library’s importance in the community. This provides historical context and brings the building to life. But what is equally exciting to us is that you can also hear visitors and people from the community sharing their own thoughts as well, thereby widening range of who gets to speak for and about the architecture of the city.

How does location-based audio enhance architecture?

So often we forget how important sound is to our environment until there is a sudden shift. Everyone has had an experience where a change in music completely energized (or killed) a party. We often take the sounds of a city as a given—but they are there by design, whether thoughtful design or not. Billboards, plaques, signs, etc… are always present, teaching us or guiding us to perform in certain ways, and the same is true for sounds. What is exciting about Hear/Here is that we can insert specific soundbites in a curated way to enhance the experience of the city and the exhibition in specific ways. The sound files are there to educate, describe, and bring joy to the city, but there is also the lovely ambient background music which facilitates a calm meandering through the city.

What were the challenges of implementing an audio AR component to your exhibition?

The biggest challenge for us is making the barrier of entry to the app as low as possible. Nearly every design decision about the app was made with the intention to create as easy and inviting experience as possible. As an outdoor exhibition without one singular entry-point, our guides are very important as they are often the main way visitors receive information about the exhibition. Even with our best efforts, we still find that some people miss the instruction to download the app or do not understand how to use this technology. If there isn’t someone there to help them in that moment, the opportunity is lost and it can result in a frustrating experience. We work hard to ensure there are a lot of ambassadors to our exhibition that can support visitors as they experience the exhibition.

Do you see a future in which digital augmentation becomes a significant part of spatial design, including architecture? How so?

Yes I do. Unfortunately, I imagine this most likely implemented for advertising in a more invasive way than billboards and signs currently fight for our attention. I imagine the science fiction streetscapes as seen in Minority Report or Blade Runner 2049 as being quite possible. As the “Internet of Things” comes online, more and more items are hooked up to massive networks—to us and the data we make and desire—and the ability to make much more responsive and adaptive design will become cheaper and cheaper.

In the 1980s, MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte was being laughed off for the idea that touch screens would become pervasive, and here we are. Our phones are interfaces to our networks. This is increasingly true: our watches, thermostats, TVs, etc… Soon our walls will be as well. And just as our phone design became all about how to feature their screen and make that screen as interactive as possible, the same will happen with those walls.

Interview with Michael Epstein

Halsey Burgund: I am speaking today with Michael Epstein of Walking Cinema. Our paths crossed a few months ago back in Cambridge, MA at the Media in Transition 10 Conference at MIT where I was doing a performance and Michael was moderating a conversation called Journalism, News, and Civic Participation. He attended our event called Democracy Performed and had some fascinating questions about audio in space and how we were thinking about moving bits of audio around the room.

So I wanted to talk further with Michael to learn more about what he is doing with Walking Cinema and how he is using various audio AR techniques to accomplish narrative, journalistic and documentary goals. The first question I wanted to ask you is a high level one: Do you have a definition of audio AR?

Audio is the most visual medium. – Ira Glass

Michael Epstein: No, I don’t really have a strict definition of what it is. And I think we had a discussion before about how I might not fit into the interactive audio category of audio AR in that most of the audio that I produce is linear and it can be triggered by your GPS location, but it’s not really reactive to the environment. But I do think, and this is an Ira Glass quote, that “Audio is the most visual medium” in that when you’re listening to a really good audio story, your mind gets triggered and starts visualizing what’s going on. That to me has really been a strong thread for the kind of productions that I do and in the richness of the sound bed that we try to create. In outdoor media projects, we really try to use audio to make the environment feel complicit with the story that’s being told. And I will go more into that later, but I think that’s really my general definition of how I work with audio and in the real world.

HB: Yeah, that’s great. I’ve been having a hard time specifically defining audio AR and I do think that the interactivity is often times a part of it. I would argue that a lot of your work that I’ve become aware of does have interactivity in the sense that audio is location-triggered and related to that specific location. There is something simply with geo-located audio that I think falls into the category of audio AR. It’s not quite as in depth as directional audio, perhaps, which is another possible layer, but there is a direct interaction between the listener and their environment.

When we emailed back and forth you used the phrase “AR audio” and I always call it “audio AR” and I think those are actually different things. A lot of your work seems to be audio which I would define more as audio that enhances a visual AR experience versus audio that is itself the primary content of an augmented experience. Am I getting that right in terms of your work?

ME: Yeah, I mean, I’d say it’s more of audio plus AR, is the way define it. And the AR being a visual overlay to your camera’s view finder that either has its own audio associated with it or works with the audio soundtrack that’s playing during the experience. So I put a little plus sign in there. But AR audio also fits what we’re doing. I think what’s interesting about this moment in what you’re doing with AudioAR.org and in these discussions is that nobody’s really great from what I’ve seen with fusing an environment, especially like a real live moving environment, with augmented reality, especially with putting something visual on top of your real world surroundings.

I’m sure you’re familiar with some projects where it’s like, wow, you can do this really cool augmented reality projection onto your living room table and you’ll see these little characters running around and you’ll experience a piece of history or an animation or a cartoon. You know what I’m talking about; the kind of standard, Magic Leap demos. And it’s just your actual living room, or possibly where you might actually be standing in front of a historical site, but either way it tends to be a really clunky integration of the real and the overlay. And so I think whether you call it “audio AR” or “AR audio”, I think the main challenge is how is that audio working in a specific environment?

And with your work, with discussions around democracy and things like that, it was really cool how you hijacked that classroom. You did quite a bit of prep to make that space work for you in terms of the way that we’d hear the sound. But also I think in some ways, to almost plot out where certain characters or questions or voices could be heard and how they could be spatially set in that room to really work. And it’s the same thing in my work when I’m saying, okay, well now we’re going to have a story being told in these specific places. I’m thinking about, what does it feel like for somebody to be in that place? Is that an intimate place? Is it wide open space, and also what kind of serendipitous things might happen in that space that we could integrate into the story?

Audio AR for Narrative

What you start doing is making people aware – when they move through the world, when they look at things and start thinking more critically – even if it isn’t specifically part of the production.

So really what is the maximum for our storytelling is when the whole world seems like it’s in cahoots with what’s being told rather than as a kind of stage that’s been taken hostage for your little show to go on. And that to me is really important with nonfiction; is that you’re trying to get, at least with Walking Cinema productions, the idea that there are very important stories to be told in history and in current events, and if people can feel like those things are not remote – they’re not something that’s in a show or on TV, they’re things that are in the world around you – what you start doing is making people more aware when they move through the world, when they look at things and they start thinking more critically. Even if it isn’t specifically part of the production, the production attunes you to that fact that we’re not so distant from the things that we care about or the pieces of history that we want to learn more about.

So really what is the maximum for our storytelling is when the whole world seems like it’s in cahoots with what’s being told rather than as a kind of stage that’s been taken hostage for your little show to go on.

HB: That’s really interesting to hear you say about that about stuff that happens in the real world around the people who are experiencing your pieces. You can’t control that. Obviously there’s this integration with the real world, with location-based controls and perhaps some directional controls, but you don’t have control over what cars drive by and what other stuff happens. But therein lies the excitement of building something that integrates with a kind of diversity of possibilities that might happen. I know I try to build in those “error bars” and put them into the composition process.

I love what you said about this notion of the world being in cahoots with your personal experience at the time. And I think that’s a really beautiful way of thinking about it. It’s interesting because a lot of times people use audio – and I think this is a very wonderful use of audio as well – but, they use audio to sort of pull, to sort of create a place to make you transport from wherever you actually are to somewhere else. Like, oh, there’s the beach, I’m hearing the wind and the waves or whatever. That can be very effective, of course. I think that gets back to the Ira Glass quote a little bit, but it’s interesting because I think what you and I both do is figure out how not to locationally transport people, but rather how to enhance the physical nature of where they are at a particular moment.

ME: And I think one of the surprising techniques in making audio more immersive is thinning it out in certain places. Rather than having that urge to create an entire environment with the audio. If you’re in a very active and activated environment and do something really minimal with just a synth, you can bring that space more alive by doing less with the audio, by letting it just be sort of a mood bed rather than information or a highly dense composition. And I think there are moments for both in what we produce. We definitely have a story to tell. We definitely need to do narrative. But what we work on a lot after we get the story down is kind of ripping open of this story and creating these gaps where people can just be walking through space and letting some of what they’ve heard sink in; or letting the environment speak to the story rather than the actual audio.

HB: Oh, I love that. That’s the interstitial moments; like you said, the walking between or transitional ones. Can you give an example maybe in Museum of the Hidden City or another project where you’ve had to really think about where the moments are where less is the right approach and where more is the right approach?

And so the discovery of this jewel right in the middle of the city and being able to walk through that is really important. It’s also important to give people space as we complicate that environment with the story of what used to be there, how it used to be a thriving, multi-generational African American community.

ME: Yeah, well one moment comes when audiences walk through a housing development that was designed after Frank Lloyd Wright, that has this beautiful cedar lined lane with a series of fountains sort of bubbling in the middle of the sidewalk. Partly what we’re trying to show is that the designers wanted to create the tranquility of the suburbs right in the middle of the city. That it was like this big coup that they’d bring back white collar workers to the city by creating a semi-suburban environment. So letting people enjoy the peace and the surprise of this place that a lot of native San Franciscans didn’t even know existed. And so the discovery of this jewel right in the middle of the city and being able to walk through, that is really important. It’s also important to give people space as we complicate that environment with the story of what used to be there, how it used to be a thriving, multi-generational African American community. So those two contrasts are, I think, both accentuated by the sound of the fountains. We do have some fountain in our actual sound bed, but we also leave a lot of space for just the real fountains to talk and respond to the stories that are being told.

HB: Right. And the real fountains are “talking” perhaps in a somewhat unpredictable way? I don’t know if there’s a schedule for the fountains or if there are times when the fountains are off?

ME: They are pretty much on all the time. The other thing too is that it’s a story of a failed utopia. And part of that Utopian thought was that people didn’t want to be on noisy, busy, congested streets. They wanted to be in these idyllic green spaces. You’ve probably heard the reference of Towers in the Park, which was what these projects initially were designed as. Oh, wow, we can go vertical and build a lot of housing units in these high towers and then around them we’ll have this park-like space where people will play. And it just didn’t work that way because for people to go to spaces, they actually need to buy stuff or have commerce going on and traffic actually helps add a little more mood and life. So these spaces that they created, these beautiful green spaces right in the middle of the city, are empty. I’ve walked this route a hundred times; they’re always empty. And so allowing that emptiness to also penetrate the soundtrack is important too. You could say it’s really empty and nobody uses it, but if you just use some silence and ask people to look around them and see what’s happening and 99% of the time it’s nothing? That is so much more effective.

HB: So you actually use silence. Do you bring it down to some very mundane drone or very slight sound? Or do you actually just pull it out completely to silence sometimes? I imagine that’s quite an effect. When you’ve been immersed by audio from this experience for a while, then to pull it all out.

ME: We never pull it all out. Though talking to you, I think that would be a good idea.

HB: Yeah. Who knows? It might be. It’s all about experimenting. That’s really cool.

Bringing Audio AR Off-Site

HB: One of the things that I was interested in with your Museum of the Hidden City app was that I experienced it when I was not in San Francisco. I didn’t have the pleasure of walking around with these fountains and all the other locations. But your app still does communicate certain bits of content and it still does some of the visual AR. I’m wondering if that must’ve taken a lot of deep thought about how to, and whether to, allow for this because accessibility is so important, right? You don’t want to build all this wonderful content that people have to fly to San Francisco to experience, but you do want to have people who are there be able to get this really extra amazing sort of confluence of physicality and audio. Can you walk me through a little bit of your thought process there?

That’s really cool. One of the things that I was interested in with your Museum of the Hidden City app was that I experienced it when I was not in San Francisco. I didn’t have the pleasure of walking around with these fountains and all the other locations. But your app still does communicate certain bits of content and it still does some of the visual AR. I’m wondering if that must’ve taken a lot of deep thought about how to, and whether to, allow for this because accessibility is so important, right? You don’t want to build all this wonderful content that people have to fly to San Francisco to experience, but you do want to have people who are there be able to get this really extra amazing sort of confluence of physicality and audio. Can you walk me through a little bit of your thought process there?

ME: Yeah, it’s really a big challenge and it’s a really important one because if there is a fairly simple way to create a remote experience of location-based audio or location-based AR, that’s huge. That’s what broadcast media is all about, broadcasting all over the world, right? And it’s easy to do that now, but it’s not easy necessarily to retrofit something that is specifically built to a site to be experienced off site. So there are three ideas that we have around this. We got funding just to do the location based version, but I do think in the next couple of months you’re going to see a non location-based version of it. And the simplest one is using any kind of 360 video platform, be it YouTube or some other platform, where we basically film the entire walk in 360 so that somebody who is listening remotely, either through the app or online, can hear the story, see the augmented reality layered on top of this video, and basically do their own armchair walkthrough of the experience. Not great, not ideal, but probably better than what you got just listening to the audio and maybe looking at some pictures of the site as you’re sitting at home.

HB: So would that be a fixed video, essentially a 360 video, but a fixed one? Or would that have the ability for the user to pause in certain areas as they would if they were walking through physical space?

ME: I think it would be scenes where actually people have 360 degree stills, that maybe have some movement to them, and they’d basically be looking around at the different stops and be able to hear what’s going on and maybe be able to move through like a church or down a street, things like that. Some people really enjoy it. I’ve done it with other projects and the augmented reality is really cool.

HB: Totally. And with 360 stills, the resolution is so much better than the video that in some ways a 360 still with audio that “moves” is way more interesting than the distraction that can happen with lots of moving parts in video.

Complementary Formats

ME: I think the other one is a transmedia approach and I don’t know, do you still use that term transmedia?

HB: Oh gosh, I don’t know. Maybe that makes me sound old to use that! I don’t know exactly.

ME: Well you sound old and nobody’s quite sure what you’re talking about anymore, basically. Good transmedia doesn’t repeat a story from one platform to another. So it’s not like you’re just re-versioning, you’re actually extending the story world. And so the other possibility, and this is something we’ve discussed with Audible, is doing a podcast or audio book version of the story that you heard, that’s site-based but really digs into a couple of the characters that are mentioned there in the site-based experience and go deeper with them. Specifically the character of Justin Herman is really interesting, and in the on-site version, he pops up as this well-intentioned, but tone deaf, developer who really just wants to turn the Fillmore into middle and upper middle class housing and screw over the African American population.

But his story is much more complicated than that. We weren’t able to get into it in the walkable version. So something like a podcast is a chance to really go into this complex character; a character that’s still being grappled with in San Francisco 50 years later. In fact, they just changed the name last year of Justin Herman Plaza to Embarcadero Plaza as part of a protest against what he did 50 years ago. So his story is still being debated and I think there’s something very topical that could be done on him.

So it’s not like you’re just reversioning, you’re actually extending the story world.

There’s also the character of Wilbur Hamilton, who sadly just recently passed away. A retrospective of his perspective and his relationship with the man who turned into his brother-in-law is a fascinating story too. These are two African American, civil rights leaders in their communities, but they stand completely on opposite sides of the fence with regard to a redevelopment of the Fillmore neighborhood.

HB: Wow. So you basically you have to do a marathon if you wanted to locationally experience the depth of these two stories. So the notion of bringing those into a more narrative form, i.e a podcast made it all make sense.

ME: Yeah. And I think people should get mad about this statement, but I think it’s very hard right now to tell complex, nuanced stories that need quite a bit of framing in a medium where many of your users are just doing it for the first time and trying to figure it out. So those are some of the reasons we shied away from the gray areas of the characters.

HB: I think about that so much. I build apps for my work as well and I always go under the assumption that there is no such thing as a “power user”. Everybody will be using this for the first time. Just assume that and present things as simply as possible, both functionally and from a content perspective. My work is probably generally a little more obtuse than some of what I’ve experienced of yours, but I think that’s pretty smart. Hopefully, maybe in a few more years, people will get more comfortable with audio AR generally.

People are certainly getting more comfortable with podcasting but that format is, as you know, not all that different from broadcast radio of course, other than the asynchronicity of it. But there’s something new about the podcast players that people seem to just take a little while to get used. I was actually listening to a podcast yesterday, which was a discussion between, Michael Lewis, the author and Malcolm Gladwell. They went into this big discussion, which I found fascinating, about how there are some stories that really make sense to tell in a podcast and could not be told in a written piece on the written page, and others that are vice versa, that can absolutely be told on the written page very effectively, but would not work at all on a podcast.

Against the Rules: Bonus Live Episode: Michael Lewis and Malcolm Gladwell

Being authors who are used to the written page and then getting into podcasts, they had this interesting discussion about what those differences were. And it had a lot to do with character and how in some cases, during a podcast, you can just let an interesting character, someone with an interesting voice and style, just be recorded. Whereas trying to bring those characteristics out in words that aren’t spoken by the character can be very difficult even for them, both clearly very accomplished writers.

I think that speaks to the transmedia approach; some formats are much more effective for certain things and not for others. For me, I like to think about it from the start of a project to the extent possible, you know, given funding and all the other restrictions that exist in the real world, so then you can design it with that in mind rather than – I think you used the word “retrofit” a little while back – retrofitting which is always problematic, at least in my world. I understand the desire and I understand the tendency to want to; if you do something successful in one medium, you want to make it more accessible to more people. It’s like, oh well we could just take this and do that with it or whatever. But I think what you’re saying is yes, you can, but then it has to be different too. There has to be some kind of additional pay off taking advantage of the new media that you’re transferring into because they all have their own benefits.

ME: Yeah. Well, one medium that also seems to be a good fit for this particular story is a live documentary like Sam Green‘s work. What Sam Green does is he makes a documentary film that audiences watch in a movie theater, but the film is designed to be narrated live, to have live music accompaniment and sometimes other additional live experiences on the stage in front of the movie screen. And I actually think that creating a film, first out of just the footage from the neighborhood, the place itself, but then also some of the historic video that we found, could work really well in the movie theater experience. People would want to watch that film. But what’s great is the talent that we have doing the voicing for the project, our two young dynamic spoken word poets. So them actually performing original spoken word poetry that they composed for this piece that plays out in the site-based version could work very well as a live theatrical version.

Also the original score was done by a producer who does quite a few live performances himself. So there is the possibility that this could be fairly easily converted into a live documentary experience.

HB: That is really interesting. What about immersive theater? I mean, there’s all these projects where you’re walking through the street and then real actors come up to you and interact to convey a narrative. This of course starts narrowing down the accessibility in an extreme way, which is always unfortunate, but can be a remarkable experience.

ME: It’s weird. We’re on the same wavelength here. I think immersive theater takes a lot of work to do it well. Though I’ve experienced things that look like they weren’t workshopped for too long and came out pretty well, but if you really want to do it right, I think you need to spend quite a bit of time getting the site for the immersive theater ready. And one site that appeared to be a great piece of the story that we couldn’t really get into in the walkable version is the story of Jimbo’s Bop City and Waffle House, which was one of about 30 jazz clubs that ran up and down Fillmore Street. They were just dying out at the point where the story that we’re telling starts in the early sixties.

And these clubs were interesting in a few ways. One was that they usually opened around midnight because they featured Black musicians who would go and play in the white clubs in downtown San Francisco and then do a second show late at night at a jazz club for their Black audiences on Fillmore Street. They played from say midnight to 6:00 AM. One of the best venues was a place called Jimbo’s Bop City. They literally served fried chicken and waffles at a small lunch counter. And then in another room (always decorated for Christmas for some reason) was a small stage with seating for about 20 or 30 people. There was a house band that played with the visiting musicians but it was really competitive. If you weren’t with the beat, Jimbo would come over and take you off stage.

HB: Well, you gotta be off the beat just the right amount, right?

And so the place became important because it was supposed to be torn down as part of redevelopment. But it was one of the Victorian buildings that was literally lifted up, put onto a giant platform and moved down the street out of the way of the wrecking ball. And so it ties in to the story that we’re talking about. The destruction and the attempted salvation of the culture and the neighborhood.

ME: Yeah, right, you gotta be in between the notes not off the notes. And so the place became important because it was supposed to be torn down as part of redevelopment, but it was one of the Victorian buildings that was literally lifted up, put onto a giant platform, and moved down the street out of the way of the wrecking ball. So it ties into the story that we’re talking about, the destruction and the attempted salvation of the culture and the neighborhood. And you could imagine that recreating Jimbo’s Bop city in some sort of space in San Francisco, where you’re not just experiencing a show of live jazz and maybe food and drink, but you’re also getting hints, a la Sleep No More, where you’ve got a bunch of documents kind of strewn around the place of who’s who and who’s trying to do what.

The club is facing trouble by both redevelopment and by the decline of the African American population in the neighborhood. Many of them were leaving San Francisco because the jobs were drying up after the war-time industries began to ramp down. So there’s a big opportunity to do something like that too. I’d love to do that. But you know, just getting one platform done at a time is hard enough!

HB: That sounds so amazing. What I really like about those sorts of productions is when you come out of something like that, you’re done with it, so to speak, but you’re totally not done with it. The whole world-building that happened within the immersive performance, as soon as you go back to the world that hasn’t been built for you, it still feels like it has been. You’re left with this ability to notice more and to think about things more closely and with a new perspective. And I think that’s what makes art so great; those kinds of experiences have the ability to stick and can be super, super powerful if done right. But like you said, this is hard stuff.

So how might journalism make use of audio AR?

ME: What interests me in journalism is that there are some big stories that I think audiences can feel detached from just because the solution seems so far away. You could talk about environmental crises this way, or the housing crisis. A lot of readers and people who follow the news are aware of these issues, but the solution seems so distant that they disengage. I think there’s an opportunity with location-based AR and location-based audio to give people a physical and first-person experience of an issue right in front of them. And in some ways it’s exciting and it’s deep and it’s cool to get immersed in that issue without feeling a weight of “Oh my God, I have to slog through a long form article on all the problems that are happening with the environment to be aware of it”. And then step away from it more depressed than feeling like there are solutions. I think that there’s opportunity to do something like that in journalism with big stories. Again, you run into the problem of to what degree is it site-based or isn’t it site-based? Are there ways you could do it in your own living room? That would be interesting. Those are all questions still to be experimented with, but I think this idea of journalism taking on big issues and using new platforms that can draw audiences is promising.

HB: Definitely. And I think the absolute versus relative location is one of these big sorts of questions that you just hit on. Is there a way to translate a location-based experience to a location wherever the listener wants to be and still be meaningful? I’ve been doing a lot of experimenting and thinking about that. I think there are fruitful ways of progressing down this line that may yield really interesting stuff.

ME: One example – this came from our proposal we started for a large utility company in Massachusetts a few years back – the idea was they send out a reminder every winter of ways that you can insulate your house. That could easily be a mini AR documentary that runs in your home. Where can you find a window? Can you find a door? And then one could layer this story on top of those household objects which moves you into this process of properly insulating your home. Something like the environment and recycling and what you can do and where greenhouse gases come from; all that could also probably fit into anyone’s home. Similarly, if you’re going to do an exposé on a company like Walmart, audiences could go to any Walmart and probably find similar objects and spaces that could be designed for AR.

HB: I was thinking about this idea as a piece on sports; go to a baseball field or something like that and press play when you’re at home plate. I think there are certain physical objects or physical spaces that are stamped out in our current society that could be used to tell a more general story in a more ubiquitous and accessible, yet still place-aware way.

One final question, can you let us know where best to find more information about your work and experience some of your projects?

ME: The website is walkingcinema.org. There you can see past projects and current projects there. The project we discussed in San Francisco, Museum of the Hidden City, is www.seehidden.city. I also have some non-interactive work up on Audible and Amazon Prime.

HB: And are there other apps that are downloadable that people can access?

ME: At this point, that’s the only one we have in the App Store. There are two other projects in the Boston area we are releasing later this year, but again, if you just look for Walking Cinema on the App Store, you’ll find it. And then in the Android Play Store, Museum of the Hidden City should be coming out in September of 2019.

The Audio AR Industry – Q3 2019

I am just coming around to thinking of there being such a thing as the “audio AR industry” and not just esoteric artistic explorations. This report by the folks over at ARtillery Intelligence shows how much things have changed over the past few years as some very big players are realizing that augmentation for your ears has a ton of potential.

HEARABLES BROADEN THE AR SPECTRUM

I have not read the entire report because it is a professional research report that is sold to interested corporations for more than I can afford, but here are some nuggets from their announcement of the report as well as a short video that presumably summarizes their research.

You can think of AirPods today like the first iPhone before the App Store came out.

Mike Boland – ARInsider

Altogether the revenue opportunity for audio AR apps will grow to $3.46B by 2023.

Mike Boland – ARInsider

Sonic Succulents

As a keen, but amateur field recordist, I was excited to see an exhibition advertised at Brooklyn Botanic Garden called Sonic Succulents. Created by Los Angeles–based Adrienne Adar it promised handmade sensors would amplify familiar plants so we could hear them through gentle touch and sound. So excited was I that I dragged my partner, my radio producer friend and his mum along.

The first room had headphones next to a range of plants, a fair few of them cactuses. There was a lot of hiss to hear, and not much else. You could hear something if you pinged the spikes of the plants, or tapped them, but you couldn’t really hear much else.

Similarly we strained our ears to hear corn growing through large yellow cones and failed. Farmers apparently have said they could hear this without the cones. Regardless it was a quite an underwhelming exhibition all round, redeemed only partially by the delicious elderflower served in the cafe.

The Deep Listener

The Deep Listener is the winner of an open call, put out to artists early this year, asking for projects which imagined city spaces in AR to be deployed on site at London’s Serpentine Art Gallery. The Serpentine is a prestigious gallery, with an extension by architect Zaha Hadid, and it hosts some of the major contemporary art exhibitions of the city, so when I heard the project was an audio AR project and involved field recordings (at least that is what I assumed “organic source material” that was mentioned on the site’s blurb meant), I was quite excited to check it out.

I visited the Serpentine not long after the app launched accompanied by two art loving friends. They are not audio AR aficionados, like me, however they do love art in all forms, highbrow and lowbrow, and both work as developers, so are keen on art/tech combos. Unfortunately we were all disappointed.

The piece is site specific and the app has a map which tells you where to go to listen to the audio recordings. We found the first easily – plane trees – but it became apparent immediately that it was going to be hard to hear the recordings as both the phones we had managed to download the app onto (one of them apparently wasn’t modern enough for the app) glitched horribly.

The idea of the piece made by Danish artist Jakob Kudsk Steensen, was to allow audiences to journey through Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park to both see and hear five of London’s species: London plane trees, bats, parakeets, azure blue damselflies and reed beds. My friends were baffled by the visuals which neither seemed to represent the animals or plants, or to be an artistic representation of them. I felt slightly kinder towards the artist knowing how hard 3D modeling can be.

The sounds were tightly built around five points of the park and it could be tricky to find them. Some were discernible field recordings – the parakeets for example, or the hydrophone recorded reed beds. The bats, damselflies and plane trees Steensen had taken more artistic license with, sounding more composed. Both approaches were fine, but I found the piece sonically incoherent.

I also found it lacking the immersion I had been promised. There were large gaps between the content which threw me from the experience. All in all, I was disappointed by what appeared on all accounts to be a major commission. I liked Steensen’s concept, but the realization of it was distinctly underwhelming.

Living Symphonies

Living Symphonies is a spatialized generative audio composition, broadcast on speakers in London’s Epping Forest as part of the Mayor of London’s National Park City Festival.

Hidden in a small part of the large east London forest are speakers placed up in trees or hidden in the undergrowth, each playing musical motifs representing different plants, animals and trees in the area. These motifs change based on the weather under the theory that the weather changes the behaviors of the represented flora and fauna. This is a “living symphony”, a musical composition and installation that is meant to grow in the same way as a forest ecosystem.

The area in which Living Symphonies plays is confined, so when we visited most of the audience were sitting under the trees listening not undertaking the sonic walk we had anticipated. But once we accepted the diminutive scale, we too took our seats. The experience was rather like being in a spatialized outdoor concert; a very pleasant one at that, not in part due to the July heatwave London was experiencing. We brought a picnic with us and spent perhaps two hours listening to the various tree and animal samples as they appeared in varied combinations, re-composing themselves through the dappled sunlight.

How responsive or living the piece really is was hard for us to tell, and perhaps it was the shade from the unusually hot UK sun, but the idea that the piece was being generated in real time captivated us and we found ourselves humming what we later found out were the string tree motives as we made our way out of the forest.

Living Symphonies is just on for a week, which is a shame as it was a lovely experience. I hope they will repeat it in more parks and forests soon.

Beyond the Road

Beyond The Road transforms a music album into an immersive exhibition. As it says on the tin, it really does offer audiences “a chance to lose themselves in a multi-sensory world led by sound”.

The music is by Unkle, a British DJ, who has dissected his album into stems and samples, and placed them around the Saatchi gallery in multiple rooms layered with videos and sets created by a variety of artists.

I was unfamiliar with Unkle, but the music lent itself well to being overlaid throughout the various spaces in the gallery. Designed by two members of Punchdrunk – Colin Nightingale and Stephen Dobbie – visitors walk seamlessly from one room to the next, poking their head into chapels with pools of water and light installations, watching fragments of Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, or lying flat on white beds hearing the various music samples around you bleed into each other.

Music comes not only out of speakers but from telephones, TV speakers and a phone box. Like much of Punchdrunk’s work, the aesthetic is slightly goth and glossy and I found it captivating. I traversed the full space twice, each time having a different experience due to my physical location in the space linking up differently with the musical “location” in the looping album.

Audio AR as Memory Palace

I have long thought of augmented reality as a direct relative (or at least a not-so-distant cousin) of the memory palace, but my ideas have only been vague high-level musings, so it was a real treat to read William Uricchio’s new essay on the history of AR in which, among much much more, he dives into this territory.

AUGMENTING REALITY: THE MARKERS, MEMORIES, AND MEANINGS BEHIND TODAY’S AR

The memory palace, like the larger palimpsest of habitations, pathways, and meanings that form our public buildings and cities, was designed as a walking space of inscription and recall, of erasure and forgetting, … and of reinscription. And the workings of the palace – the method of loci– bear centrally upon the logics of locative media.

William Uricchio, June 2019

For my audio AR work, I have always relied on the connection between physical location and audio content to sear the experience into listener’s memories. And since the currency of any artist is at least in part memorableness, this becomes a useful tool. There is something about audio on location – probably in no small part due to the freedom audio leaves your eyes – that has me creating inadvertent tiny memory palaces (memory shacks?) as I go about my days.

…augmentation can also offer a process of narrative discovery, as the user finds new associations and coherence through newly sequenced encounters with their own markers.

William Uricchio, June 2019

Last summer, I was listening to the audiobook of Joshua Foer’s “Moonwalking with Einstein” (meta!) while chopping wood at the edge of my woods for many hours, and I am still always reminded of it when I walk by that same spot and look at the chopping block or see the axe. I’m not quite sure what it was that seemingly permanently attached that memory to that location for me – and neglected to do so for other memory/places – but it is in the very least a fascinating take on the potential power of audio AR. I can imagine learning or training methodologies that could take advantage of audio AR to reinforce certain desired behaviors by building memory palaces in a slightly less directed, but perhaps equally effective, way than the memory champions of the world, like Joshua Foer, do.

William’s essay contains many more insights and I highly encourage you to read the entire piece, but I will leave you with a few of my favorite quotes to ponder.

At a moment when terms such as ‘virtual reality,’ ‘mixed reality,’ and ‘augmented reality’ are being tossed around as much as marketing banter as aspiration, it may help to think more broadly and even historically about the endeavors underlying these claims…

Similar to the method of loci’s transformation of location through the addition of associations, ‘place,’ once situated, historicized, and laden with meaning, emerges as ‘space’; and the ‘map,’ once interpreted, contextualized, and larded with meaning, emerges as the ‘tour.’

…markers overlay the streets and doorways of the material world, providing a palimpsest of associations at once residual, well-rehearsed, and newly acquired, but always standing in relation to a historically accreted – and publicly endorsed and indeed, declared – narrative.

Technologies will come and go, but humans will continue to mark the world, read it, and find coherence – activities inherent in augmented reality.

And if you want even more on this topic, the bibliography is a nerd’s treasure trove!

Abstract

Humans have long ‘marked’ the world, cities included, augmenting their surroundings with traces of their experience. They have learned to read the signs inscribed on the world’s surface, whether in search of prey or precedent. And they have sorted out how to give those marks coherence, whether as narrative or insight. Publically deployed, discovery-based, or even personal, augmentation’s inherently dialogic character requires reality for its work. This essay considers today’s AR technologies in terms of these more deeply embedded practices of augmentation, particularly as they play out as interfaces in urban places. It explores underlying continuities between earlier augmentation practices and our own, suggests strategies that can usefully inform our deployment of AR technologies, and points to semiotic reciprocities that can help AR move from the gadget du jour to an ally in a profoundly human conversation.

The Future of Face-Wear

I’m not sure if that is a term, but “face-wear” seems appropriate for all the crazy things tech companies want us to put on our faces as a portal into digital worlds. I have an assortment of feelings of ambivalence and apprehension about many approaches that are being taken, but overall, there is so much positive potential that I try to stay abreast of where things are going.

To this end, I just read this great article on the current and future state of hardware for VR and AR. It has been a confusing landscape for everyone with the rapid pace of development and seemingly faster pace of deprecation, and this article does a great job of laying out the basics.

SMARTPHONE, MEET SMARTGLASS. NOW TETHER.

This focusses on visual forms of augmentation, but there are implications and interesting points that can be applied to audio AR.

There is a lot of discussion of 5G and how “edge computing” will enable new, more realistic AR experiences and this is super exciting. Moving the computational heavy lifting off the device and into the cloud, while retaining the ultra-low latency of on-board processing via 5G is no doubt hugely significant if and when it is realized with some form of mass-distribution.

Audio has traditionally been way less processor intensive and hence doing audio AR has been “easier” and requiring of less intrusive hardware, but as I delve into experiments with trying to make audio sound like it is coming from a real-world point source, I realize that I may have been deluding myself.

The reason audio AR requires less processing at present may simply be because no one has yet figured out how to do it right.

There is less processing required because less is being done. After all, it takes less processing to display a janky looking pixelated tomato floating randomly in front of you than it does to create an animated Jigglypuff complete with real-world occlusion and shading. Is audio AR in the pixelated tomato phase? Yes, we can pan things generally in 3D space but it hardly sounds like a point source in most cases. And distance emulation is so much more than volume attenuation.

- Who is trying to solve these challenges?

- Are the big tech companies too focussed on visuals to put resources into audio?

- Do we need a complete makeover of audio delivery devices (i.e. ear buds) for this to be possible?

- Or will processor-enabled advances in psycho-acoustics do the trick?

I’m sure efforts are being made to address these questions and I will dive into those and report back when I can.

Check out the entire linked piece, but I’ll leave you an eloquent encapsulation of something I’ve been thinking about for many years, but only now is it starting to become possible.

XR represents a technology communicating to us using the same language in which our consciousness experiences the world around us: the language of human experience.

Pause on that for a moment. For the first time, we can construct or record — and then share — fundamental human experiences, using technology that stimulates our senses so close to a real-life experience, that our brain believes in the same. We call this ‘presence’.

Suddenly the challenge is no longer suspending our disbelief — but remembering that what we’re experiencing isn’t real.

–Sai Krishna V. K

Thank you to Scapic for sharing this!